Rizal the school designer, Shakespeare’s Ghost, and the women of Berlin

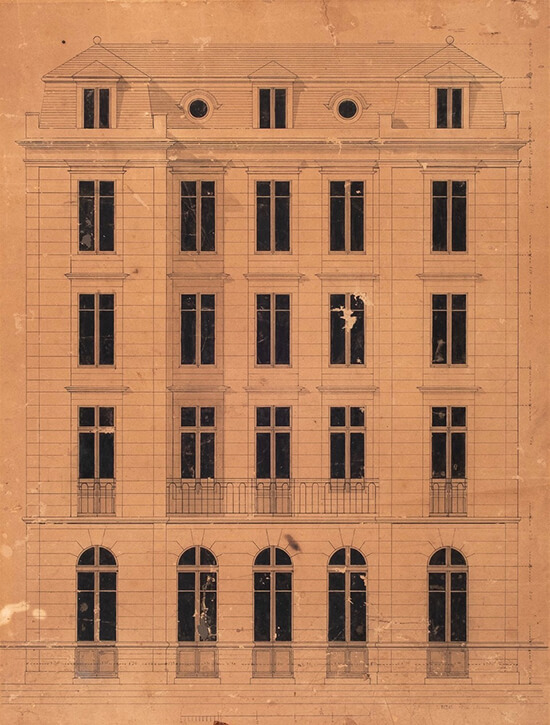

As if on cue, a newly discovered architectural drawing by no less than Jose Rizal has appeared, a coded message perhaps intended for the Department of Public Works and Highways. It belongs to the descendants of Rizal’s most-devoted sister Narcisa. (She endured Dapitan with him and gave Josephine Bracken shelter.)

It’s a detailed “elevation of the facade” of the national hero’s dream academy—and may also be something the Department of Education could consider as a peg for its schoolhouses. It’s a glorious representation of learning, much more inspiring than the anonymous-looking buildings being built for gazillions by the nation’s favorite culprits, the DPWH. Just think of it: schools designed by Jose Rizal.

Not many may recall this, but among Rizal’s many multi-hyphenated achievements was being the country’s first licensed geodetic engineer. Yes, Rizal was a surveyor of land—trained at the Ateneo de Manila when he was just 17 (but too young to be given a license until age 21). It’s a quality that now comes in handy when you think of Senator Ping Lacson’s team flying their drone over numerous ghost projects.

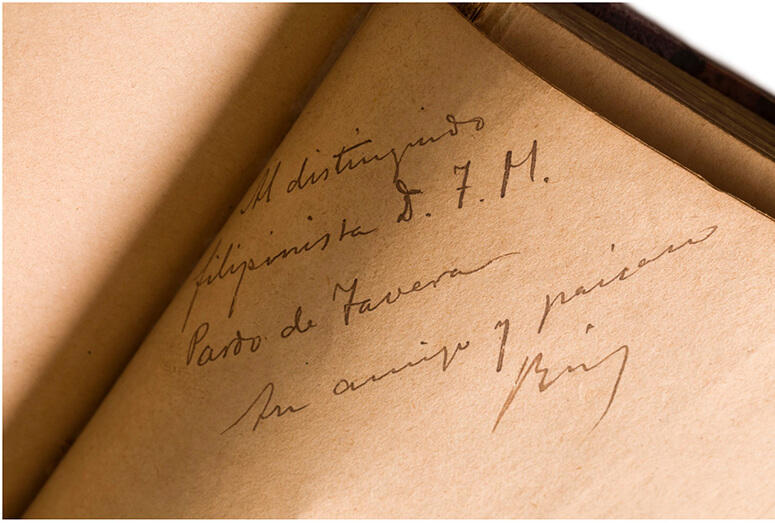

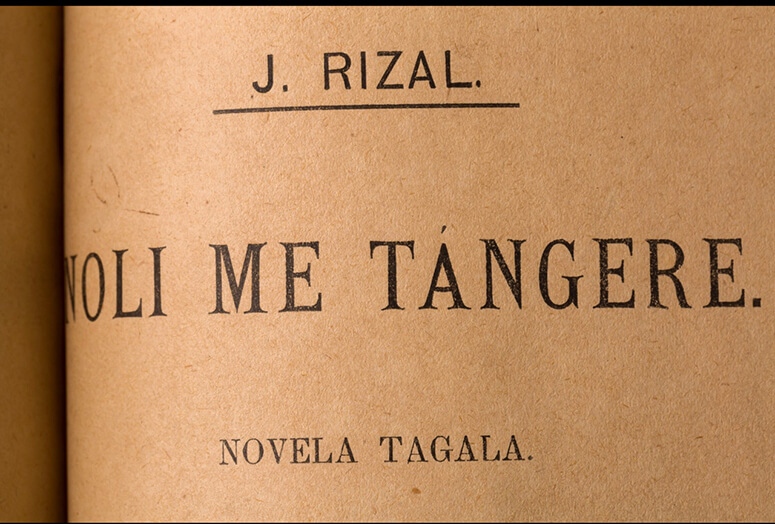

It arrives on the market in tandem with another sumptuous marvel—a first edition of Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere. This volume is a signed copy dedicated to Rizal’s fellow intellectual Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera. He was the older brother of Paz, who married another from their ilustrado circle, the painter Juan Luna. It was T.H. who lobbied hard with the American regime to have Rizal declared national hero.

So few first editions have survived confiscation by the Spanish authorities and the ravages of revolution and two World Wars. Two copies are at the National Library; this is the first to surface in several years still in private hands, where it was lovingly conserved.

Both of these treasures, the book and drawing by Rizal, will be offered at the Leon Gallery Magnificent September Auction on Saturday, Sept. 13 at its Makati sale rooms on Legazpi Street, Legazpi Village. (The public is invited to its preview week which starts on Sept. 6, 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., Sunday included.)

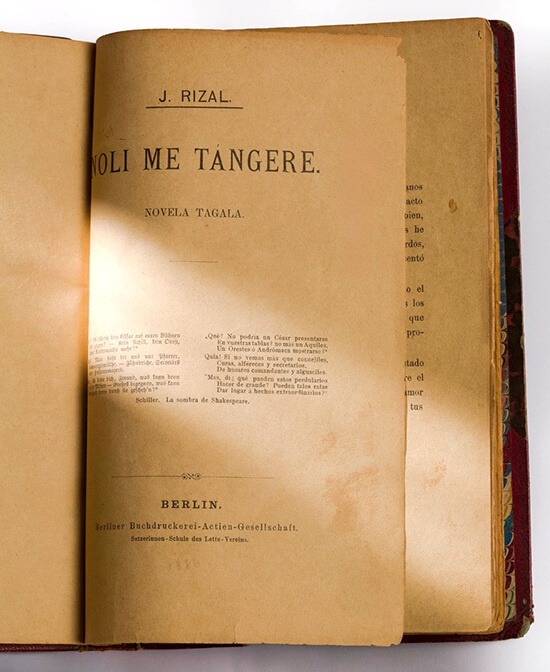

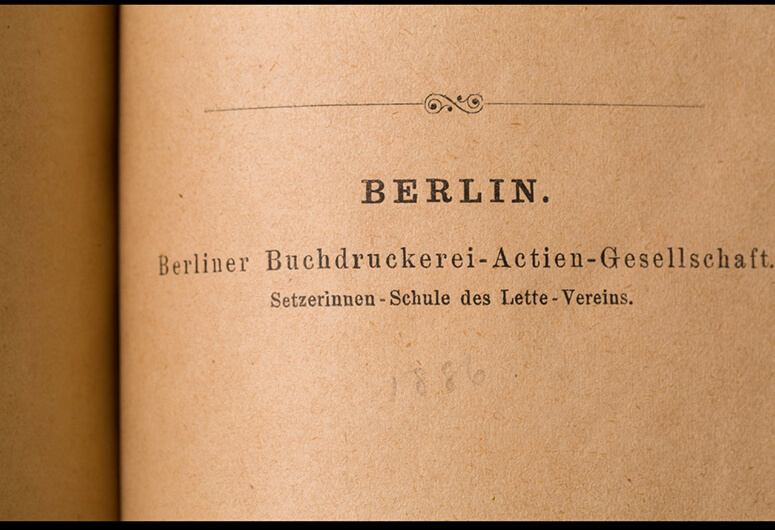

This Noli is the most important and therefore most elusive edition, printed in Berlin in 1887. Below that identifying mark is the interesting line “Setzerinnen-Schule des Lette Vereins”—and just before one’s eyes glaze over the sight of a foreign language, this translates to “Typography School of the Lette Verein.”

The impressive thing is that the Lette Verein is a pioneering women’s school to teach single females (yes, the unwed) to earn a livelihood. It was founded by Wilhelm Adolf Lette whose first inspiration was to have cooking and sewing classes. But something miraculous happened when his daughter Anna took over. She introduced cutting-edge tech skills of the time such as photography and typesetting. (This would be the modern equivalent of teaching AI and social media courses.) It still operates to this day and is famous for its photo school.

“Verein” is German for “association,” or shall we say “liga” (because this was most possibly what Rizal had in mind for the near future). In truth, it was like our Don Bosco vocational school but exclusively for women.

It was to the Lette Verein that Jose Rizal took the P300 loan he had received from bestie and traveling companion Maximo Viola and got them to print 2,000 copies of the Noli if the records are correct. (That works out to just 15 centavos per book.)

For context, Ambeth Ocampo has referenced Rizal saying, “All in all, heating, light, laundry, room and food cost me some 30 pesos a month or a little less. Add to these expenses the cleaning etc. so that for 40 pesos one can live well in Germany, if one doesn’t have to buy clothes and to travel from time to time.” In other words, the printing of the Noli cost the equivalent of 10 months’ allowance for Jose Rizal. Viola was the only son of rich landowners from San Miguel, Bulacan, and like Rizal, was sent to study medicine in Spain. His allowance was no doubt several times over that.

To the credit of the women of the Lette Verein, Rizal—who was clearly a Type A personality—found only three tiny errors in the typesetting, which he put in the last page under the mildly accusatory heading “Erratas No Faciles a Notar (or “Typos Not Easily Noticed”). It’s not hard to forgive them if you just think that the ladies were German speakers having to typeset a book in Spanish, working with letters molded backwards in metal. No easy task indeed.

Even more amazing is that the Lette Verein which still stands in Berlin to this day bears a striking similarity to Rizal’s architectural drawing of the school he wanted to build in Hong Kong in March 1892. It has the same lofty windows and high-minded scale and holds a special resonance when you think that this is where the Noli was first breathed into life. (Almost certainly, Rizal was thinking of the Lette Verein when he wrote the revolutionary “Letter to the Young Women of Malolos” in 1889, exhorting them to pursue their own dream of a night school.)

The Noli Me Tangere is so magnificent that Rizal would leave enough inspiration in just its title page to fill any other author’s entire book.

After announcing his name, indicating he was unafraid of the consequences of his writing—“J. Rizal” rides high above the title of the book and the description of what it was, a “Novela Tagala (A Tagalog Novel)”—he launches into three verses from an obscure German poem called “Shakespeare’s Ghost.”

The poem was written by the not-obscure Friedrich von Schiller, Germany’s most famous and possibly most beloved poet. (The 21st-century audience will still recognize his name as the author of “Ode to Joy” made famous in Ludwig von Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.)

In it, Schiller asks his fellow writers what has become of the heroes that Shakespeare immortalized, Julius Caesar and Achilles and Andromache and the Trojan women? He ponders that, without such heroes, “What can they do that is really great? What greatness can they achieve?”

It is clear, by the time Rizal adds this opening flourish, that he’s fallen in love with Schiller and the German way of the grand gesture. With this, Rizal throws down the gauntlet to his fellow writers but also to his readers.

Every morning for four months, before studying the mysteries of eye surgery at the world-famous AugenKlinik in Heidelberg, Rizal would also absorb the intricacies of the German language with the kindly Pastor Ullmer. (He would board for free at Ullmer’s home in Wilhelmsfeld to save money although it was outside the city limits of Heidelberg—sort of the same way a student who could not afford to dorm at the Ateneo de Manila would seek lodging in Fairview.)

Ullmer selected a work by Schiller called “William Tell” to teach Rizal German. Yes, it’s the very same story about the hero shooting an arrow through an apple set maliciously on top of his son’s head. “William Tell,” like “Robin Hood,” was all about a single rebel going up against a powerful kingdom. Sound familiar? Rizal seemed to think so; he translated the popular German play into Spanish, calling it “Guillermo Tell.”

It would be in Wilhelmsfeld, while living in the Ullmer home, that Rizal would write the last chapters of the Noli—and obviously, its very first page.

On that first page, it is now Rizal—quoting Schiller—who challenges his fellow Filipinos and asks them if they are willing to do more. Schiller is even more blunt, accusing the present generation of being only interested in “forming syndicates, lending money, stealing silver, and never fearing retribution.” It has a chilling resonance today.

One can imagine the effect these verses would have on Andres Bonifacio or Emilio Jacinto, who would begin writing their own patriotic poetry and dreaming of the downfall of the Spanish empire and the rise of a brotherhood, free and prosperous under one sun.

Rizal would thus define himself as the ultimate whistleblower in his dedication “A Mi Patria” or “To the Mother Country” in the Noli. He would say in no uncertain terms that it was his wish to “expose what is sick” and bring to light the many ills of the Philippines and lay it on the steps of the temple for all to see.

“To this end,” Rizal wrote, “I shall endeavor to show your condition, faithfully and ruthlessly, I shall lift a corner of the veil which shrouds the disease, sacrificing to the truth everything even self-love—for, as your son, your defects and weaknesses are also mine.”

May Rizal, as he continues to reach across time, remind us all that corruption—whether in Bulacan or in countless other places—strikes at the very cradle of Philippine history, destroying precious landmarks such as Malolos, the home of the First Republic, and the other sacred battle sites in every region where the blood of our heroes was spilled for our freedom.