KKK: When banking and art come together

From the mean streets of Manila to a delicate child’s frock, then on to totems and kettles, as well as images of pillows and windows, the exhibition “Kultura. Kapital. Kasalukuyan.” features a mighty selection of 35 works from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ collection of Filipino contemporary art created by today’s most influential artists. It opens to the public on Aug. 15 free of charge, at the National Museum of Fine Arts in two of its spacious galleries. It will run for more than two years until Nov. 15, 2027.

Banking and art have been familiar bedfellows since the Quattrocento when the masters of the coin, the Medicis, decided that they would pursue that greatest sport of kings, the commissioning and collecting of art. Then as now, the ownership of beautiful objects defined not just one’s identity, but also one’s importance in the hierarchy of politics and society.

The Bangko Sentral has had a long, venerable history of investing in Philippine culture long before it became fashionable in the country. “We have (former) Governor Jaime Laya to thank for setting that into motion,” says Bernadette Romulo-Puyat, deputy governor of the BSP for regional operations and advocacy. “And he’s still on our acquisitions committee to this day.”

The BSP Collection is most renowned for its holdings in pre-colonial gold and Spanish-era paintings and furniture. Indeed, it owns some of the most important cultural touchstones of the country from the 16th to the 19th century. There are, in fact, enough treasures to fill several museums. Not so well known is its glorious assets in the world of Filipino contemporary art. The “KKK” exhibition is just a small part of those artworks.

The BSP Museum has been on the drawing board for several years, says Romulo-Puyat, and it’s been a stop-start and then stop situation. (The museum falls directly under her purview.) A decision was finally made to make the art available to the public to view and enjoy. “We were simply getting too many requests for people to come and look at the collection,” she says with a smile.

At present, the works not stored in the bank’s vaults are scattered all over the institution’s premises, from its imposing lobby (which has a trove of Botong Franciscos and Manansalas) to the many private offices of the country’s ruling financial elite.) There are Lunas and Hidalgos, as well as Amorsolos and many other treasures.

Having said that, BSP Governor Eli Remolana is “a fan of contemporary art,” Romulo-Puyat points out, and his support was pivotal to the project. “He loves and appreciates art—he even paints!” she declares.

For herself, Romulo-Puyat is drawn to the whole spectrum of art, from classical to contempo. She picks out three of her most favorite works from the show: One is a pillow with a secret drawer called “Psychology” by Dan Raralio (“Isn’t this exactly what dreams are?” she asserts.). Then there are Marina Cruz’s “Spring Beauty” (“There’s something so beautiful about this!”) and “Quiapo” by Mariano Parial (“I like the two little boys peeking above the anting-anting!”).

It took nearly a year of careful curation for the project to finally unfurl itself at the National Museum of the Philippines, helmed by the Museo BSP team. The special adviser was Romeo Bernardo, who also sits on the Monetary Board.

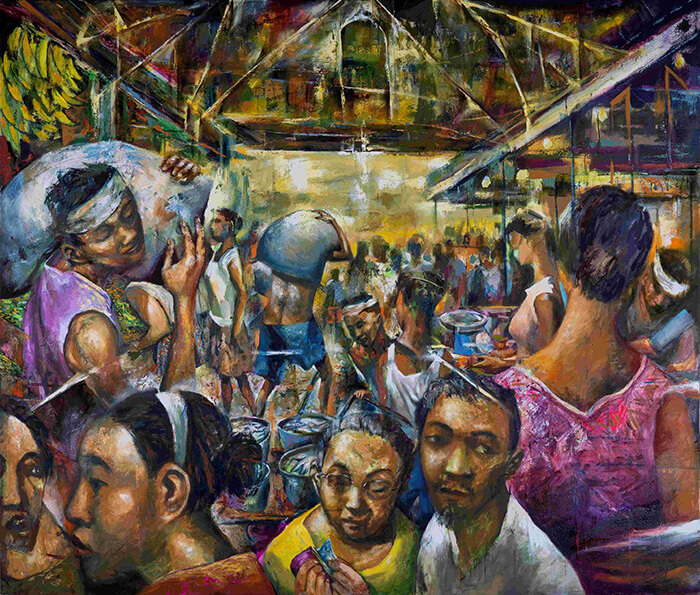

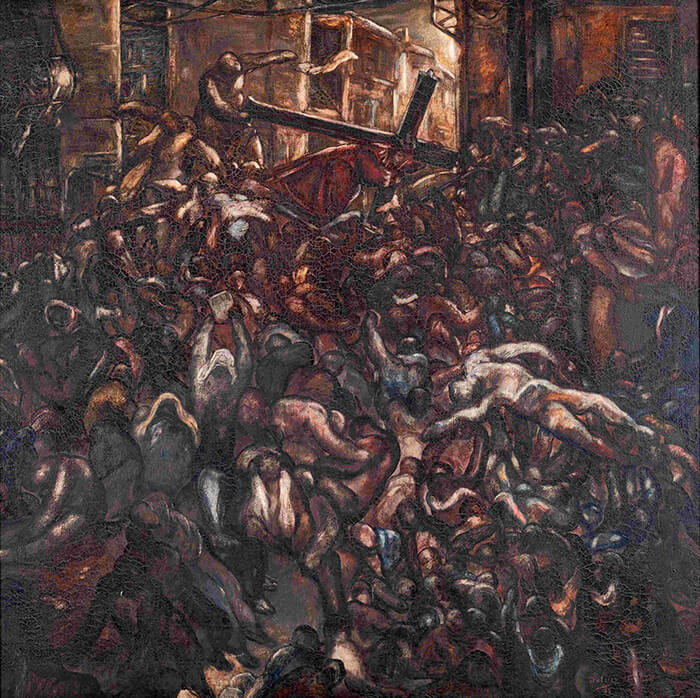

The works comprise a king’s ransom of contemporary art from such names as Danilo Dalena and Emmanuel Garibay, Santiago Bose and Pablo Baens Santos, Charlie Co and Leonard Aguinaldo as well as women painters Ofelia Gelvezon-Tequi and Geraldine Javier. It covers 50 years from 1964 to 2014.

The National Museum, like the BSP, is also famous for its legendary 19th-century works of art, most notably Juan Luna’s “Spoliarium” and Jose Rizal’s “Josephine Sleeping.” Jeremy Barns, its director-general, notes, “Most of the people you see here at the Museum are here for the very first time.” (It’s probably a happy result of its free-entrance policy and that it’s open seven days a week.) Barns would like more people to come back for the second and third time, in the same way that there are repeat visitors to see the Mona Lisa at the Louvre.

Onib Olmedo s bargirl.jpg)

What makes the current “KKK” exhibition even more interesting is that other galleries on the very same floor provide the context for the works, beginning with some of Jose Joya’s most significant works, including “Hills of Nikko,’ which marked the Philippines’ very first entry into the world of the Venice Biennale in 1964. There are other halls devoted to the other great modernist masters as well.

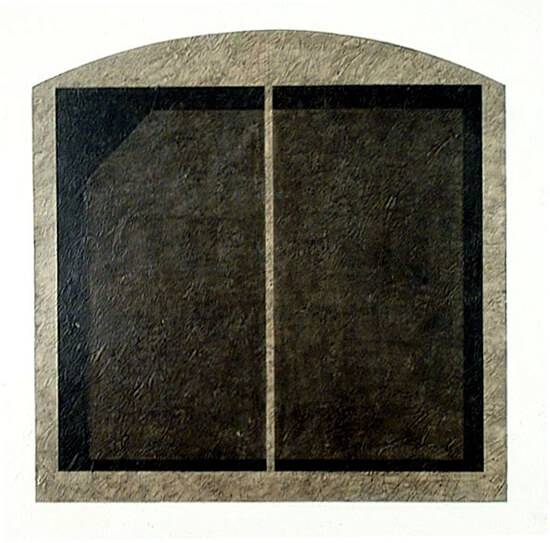

It’s the perfect introduction. The first part of the current exhibit is titled ‘Pagmulat’ (Awakening), an unabashed look at the social realism movement of the Seventies at Gallery XVIII. It leads with a classic Chabet “Window,” the earliest work in the show from 1964.

Speaking for the Museo BSP team, deputy director for corporate affairs Cecille Torrevillas-Gelicame explains, “‘Pagmulat’ (Consciousness) brings together works that reflect the everyday realities of Philippine life. Featured in this gallery are 15 artworks showing how artists responded by inviting reflections on the social issues of their time.”

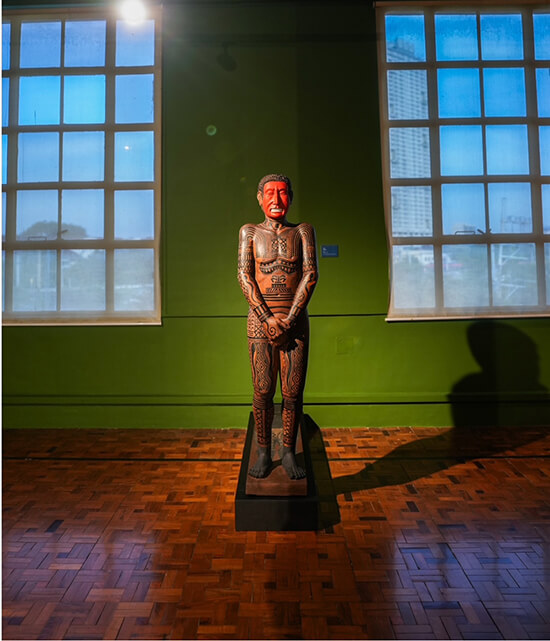

The second half of the show, this time called “Pagtanaw” (Perspectives) at Gallery XIX “looks into past realities, offering insights into emerging themes. Featured in this gallery are 20 works that explore artistic expressions that define identity, challenge inherited narratives, and affirm the role of art as a tool for critical discourse.”

Gelicame is quick to point out that it was a solid team effort led by Jay Edward D. Amatong, director for corporate affairs, supported by Beatrice Anne T. Belen-Ferrer, John Paul T. Orallo, Gretchen J. Flores, Regyn B. Avena-Alagon, Lauro E. De Los Santos, Ar. Leo R. Enano and Sophia Mae S. Pelagio.