Touching the divine in Angono

Growing up, Holy Week had always meant a trip to the beach. Consequently, this also meant remembering the last days of Lent—the smell of suntan lotion, the sourness of leftover spaghetti, along with the plaintive cries of cousins playing on the sand.

It was only later, when I had the chance to live in Angono, Rizal, that I came to know of a different Holy Week—one that was filled with fervor but also frolic.

This year, wanting to reconnect with an abundance of ceremony, I decided to attend the Good Friday rites in Angono. I was not too familiar with some of the sites anymore so a local artist, Haidee Juban, offered to accompany me. The first ceremony I joined was the Dapit sa Poong Hesus, a kind of modest procession.

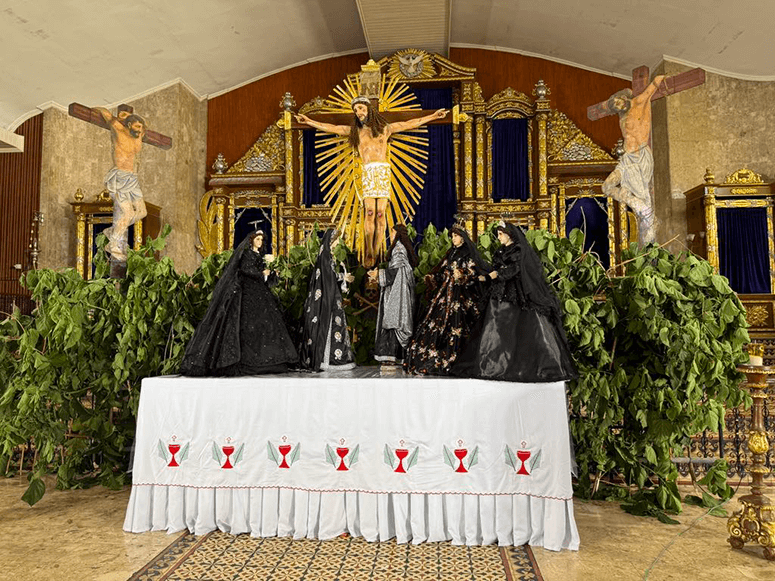

Arriving at Angono’s church, I saw that the stage had been set up. At each end, there were two crucified figures. These were the two thieves: Dimas, the repentant; and Gestas, the impertinent. The figures were painted by Juan Senson, the ancestral visual artist of Angono, who was active from the 19th century to the early 20th.

The backdrop was made up of the green boughs of the alagao tree. The leaves, which have healing properties, have a pleasant odor which may well be the scent of Lent.

The middle cross had no corpus. So we went searching in a nearby chapel. Here, on a bed covered by a blanket despite the heat and surrounded by devotees like mourners in a wake, lay the Poong Hesus, a life-sized statue of the dead Christ owned by the Fuentes family. The Poong Hesus was waiting for the contingent that would bring it to the church where it would be nailed to the cross. On the wall, like a premonition of the sacrifice to come, was a painting of the Crucifixion. This was, again, the work of Juan Senson, perhaps his masterpiece, with its stormy skies: one side was gray, the other, black, a yin-yang of grief. How clearly could one read in the faces not just anguish, but exhaustion as well.

We came upon the band members and the float bearers spilling out of the chapel yard, laughing as they ate. Then we spied the calandra, the carved vessel that would contain the Poong Hesus, being decorated with flowers by twins Carlo and Paulo Fuentes.

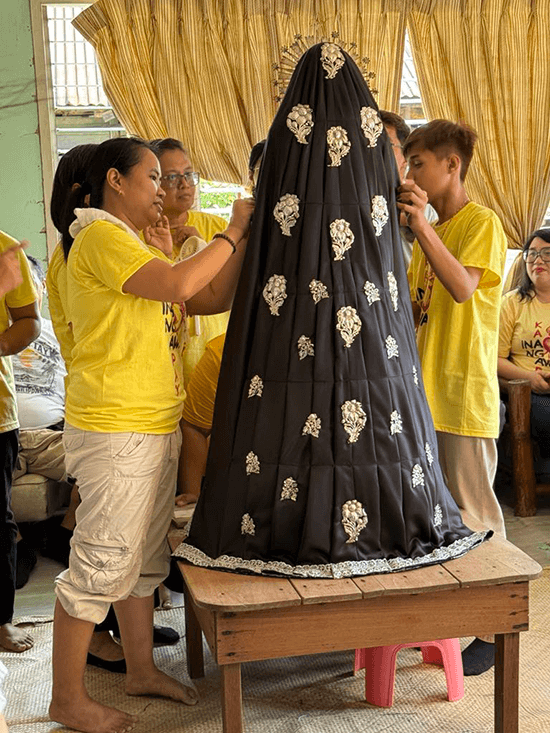

We traced the much-awaited escort contingent to its origin: the house of the De la Cruz family where resided Ina ng Awa, the statue of the Mother of Mercy. Entering the sala, we saw that Ina ng Awa’s companions were waiting: St. John the Beloved and the Tres Marias.

We climbed the steps to the second floor to find Ina ng Awa surrounded by women who were dressing the statue with black and silver garments. Inang had its back to us. Then slowly, as if steeling itself for the despair of the day, the statue turned around to confront us. It was then that we came to face the sorrow of the world.

A man carried Ina ng Awa downstairs and set it on a table. The statue had descended from an intimate space of females and the feminine, moving to the public sphere where it would be subjected to ceaseless photo-taking with cell phones. Perhaps this was the present century’s way of worship.

The chants of the public reading of the Passion or the Pabasa could be heard. These were accompanied by the relentless staccato of steel knives on wood. Out in the kitchen, the women were chopping piles of vegetables for the lumpia of the Pabasa, rolls filled with radish and carrots, innocent of meat.

Suddenly the Dapit began. Ina ng Awa and her companions were carried to the street, in the heat, in the sea of sweat, in the crush of bodies surrounded by horns blowing and the machine-gun bursts of clappers.

At the chapel of the Poong Hesus, the long, sad statue of Christ was brought out to join Ina ng Awa. I remember, as we walked to church, catching glimpses of the back of the Ina and of the Poong Hesus’ solemn face. Then it struck me. From this moment on, with this short journey in the streets, we were no longer just devotees in a procession. We had become mourners marching to a sacrifice. We were no longer just transferring statues being employed in a ritual. We were accompanying a mother who was bringing her son to his death.

The Poong Hesus underwent an interesting transformation, too: in its bed in the chapel, it was a depiction of the dead Christ. But as the statue was brought out to be nailed to the cross, it was suddenly an image of the Savior still living but soon to meet his death. Die he did as we all watched him lower his head with the help of hidden hands. Never leaving his side was his mother, a tower of ebony.

In a way, it was incorrect to speak of the Poong Hesus and the Ina as mere sculptures. They were entities that had their own lives. Surely, they were even considered members of the community.

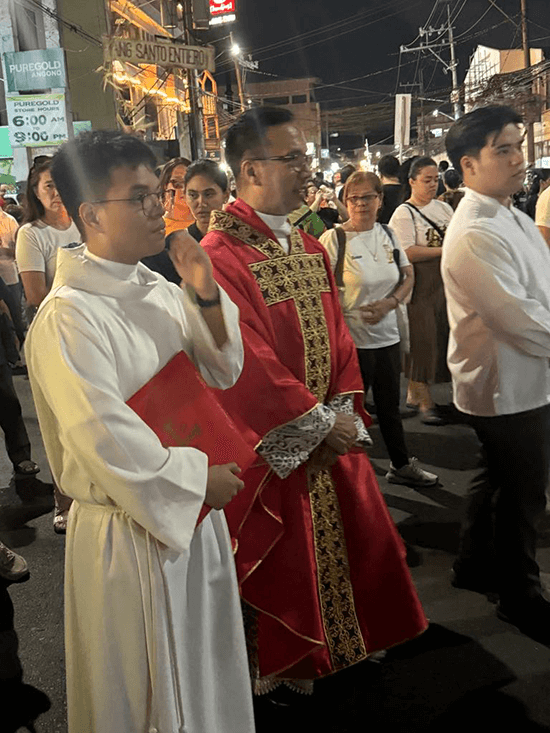

After the crucifixion so ably staged by Fr Eymard Balatbat, Nico Macapagal and their colleagues, the Poong Hesus was taken down from the cross. The townspeople lined up to say their farewells at the wake for the dead Christ. And then, the procession began. There were more than 30 floats. All either depicted tableaux from the life of Christ or personages that were involved with him. Slowly, it became clear, however, that the grand procession with its splendor and spectacle was a re-enactment, a retelling of the story of the Passion.

It was only during the short walk in the heat of the streets that we felt briefly, oh-so briefly, that our everyday lives could be touched by the Divine.