History, towards hybridity, etc.

As heralded, this piece follows up on the previous one in this space that introduced the myriad elements involved in the writing of history.

Two important titles in Vibal Foundation, Inc.’s commendable series that gives new light to Philippine history invite this appreciation: More Postcolonial Than We Admit 1: Producing the Filipino After 1946 by Charlie Samuya Veric and Emilio Aguinaldo: Politics and Remembrance (1901 - 1963) by Jose Victor Z. Torres.

As a sampler from Veric’s anthology, the preceding commentary mentioned the inclusion of two iconic creative writers: National Artists for Literature Nick Joaquin and Edith L. Tiempo. Writing on the Battle of Mactan, the inimitable Joaquin entertained with the premise that rival chieftains Lapu-lapu and Humabon formed a “twinship” of spirit. While our first national hero resisted colonization, Humabon represented acceptance.

Joaquin surmises that Lapu-lapu may have well thought of Magellan’s big ships as an extension of Chinese or Japanese intrusions. What was the supposed West of the white man to him but another version of Asian imperialism? He points out the paradox of Lapu-lapu as a tribalist eventually hailed by nationalists as “the First Filipino.” It was Magellan’s “unification of Cebu and Mactan that Lapu-lapu refused to accept.” This marked the islanders’ ambivalence, akin to “saying yes and also saying no.”

Lapu-lapu may have been the first Filipino, but so was Humabon. Together, “they were the First Filipino… not two but one, though Humabon was converted and Lapu-lapu scorned to be converted. Neither is complete without the other. Throughout our history, these two have been at work together, continuing their original dichotomy, so that it can be said that the Filipino is twins.”

For her part, Tiempo’s article on the use of English in Philippine literature cites as exemplary Manuel Arguilla’s fiction, in particular How My Brother Leon Brought Home a Wife. Sustained by quotes from American critic A.V.H. Hartendrop, she champions “a singular kind of ‘photographic’ fidelity to the native material” and “a congruity between the language and the depiction of the native ‘texture.’”

Tiempo adds: “Arguilla’s devices are happily suited… He does not set our teeth on edge as some of our present writers still do by their clumsy or careless efforts to foist off on the reader the incongruous union of ill-suited language to the material being developed…

“How should we judge the result of this fusion of two cultures? An artistically successful Philippine story in English is neither Western nor Filipino, nor yet hybrid, because it is finally neither part Western nor part Philippine material… The finished work is a result distinct from the raw material and from the medium that gave it birth.”

She concludes: “The English language has made it possible for the Philippine outlook to grow towards directions as yet unassimilated into the semantics of the vernaculars.”

On the other hand, Carmen Guerrero Nakpil’s “The Hybrid Character of Contemporary Filipino” starts thus: “We have only looked at ourselves, listened to the way we talk, noted how we feel, or write, and especially what we think to realize that our culture is hybrid indeed, that is to say, that it is a mixture of elements from different and often incongruous sources.”

Differing yet similarly invaluable views are presented side by side as provocative essays on our postcolonial passage, which may be said to yet compose a more intriguing cycle than what we subsequently entered.

It’s quite an engrossing read. Other standout contributors include Fernando Zobel, Rodolfo Paras-Perez, Resil B. Mojares, Randolph S. David, and Soledad S. Reyes (to whom, BTW, congratulations for her Gawad Tanglaw ng Lahi among the Ateneo de Manila Traditional University Awards).

The second title that merits promotion has a Foreword from the National Historical Commission of the Philippines’ former chairman, Emmanuel Franco Calairo, who summarizes the historiography on the subject before declaring, “Because of this book, Emilio Aguinaldo will no longer be misunderstood in the pages of Philippine history.” The Preface, in turn, suggests the volatility of bias conflict by leading with the re-echoed phrase: “The hero who lived too long.”

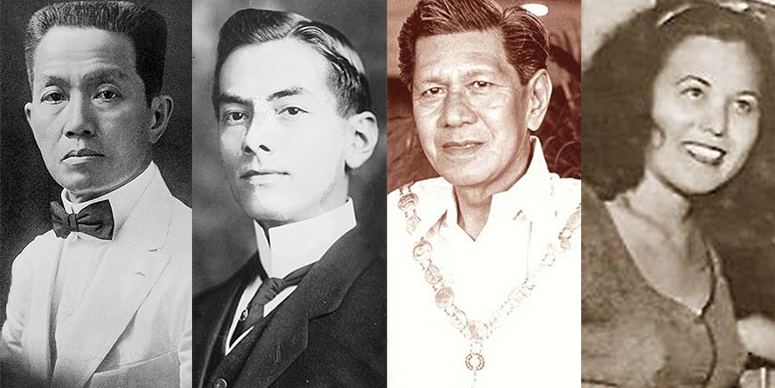

Ironies dominated his life. Rivalries with fellow revolutionaries led to accusations of a power grab, assassination, and a sell-out to the OG imperialists—all trumped by countrymen’s betrayal. Pictorially, the peak irony may have been his experience as the first Philippine President to reside in Malacañang, but as a prisoner of war of the next set of colonizers. In that setting, another eventual rival enters his life as Lt. Manuel L. Quezon, a follower then serving under Gen. Tomas Mascardo. Upon his instructed surrender so he can meet with his captive idol, Gen. Aguinaldo, the young MLQ gives up his dagger to Lt. Miller, an American officer. It is returned to him 35 years later when he becomes president of the Commonwealth.

Such tidbits and winsome turns, doing cameos in the romance of narratives, render pleasure while reading history. They ring the bell of affinities with creative literature. Picayune or picaresque, they turn out to be more memorable than the plodding march of factual occurrences.

Credit author Torres for fastidious research and scholarship—opening windows for further speculation. That, for instance, Gen. Arthur MacArthur, “the father of the hero of the Battle of the Philippines,” fulfilled an additional historical role by pointing out the room where the young Quezon could see Aguinaldo. And that very likely, decades later, MLQ told his son Douglas about his own first visit to the Palace.

Another throbbing pulse it is that stimulates the imaginative reader to savor the hive mind of history at work in its writing—akin to the subtle jumps in time in the fiction of a Garcia Marquez, a Rushdie, or a Murakami, where the apparent aside stands out as the nugget in the vein of narrative.

There’s Aguinaldo as a groundbreaking revolutionary, and the Aguinaldo who invited incessant criticism as the decades wore on. Apparently, the gapped divide owed itself to his political choices of whom to support, and how. He always found criticism on the other side.

Forwarding to the 1920s, “Aguinaldo … laid the blame for the conflict with (Gen. Leonard) Wood on Senate leader Manuel L. Quezon.” Friendship with Wood, an unpopular Governor General, escalated the feud with MLQ. It wasn’t until 30 years later that Aguinaldo had his say (co-written with Vicente Albano Pacis, on the Board of Control controversy): “The Wood-Quezon quarrel was not without its blessing…. When the Philippine and American supreme courts finally repudiated Quezon’s stand and upheld Wood’s, many of those who sided with the Filipino leader could not have missed the point. An admirable nationalistic leader, Quezon was not, for this very reason, conditioned to be a good constitutional president.”

Ironically, that last statement must have raised hackles among nationalists. It may have also come too late. In any case, the long feud climaxed with Aguinaldo’s loss to MLQ for the Commonwealth presidency. It was reported to have thawed off during a social event early in 1941, where the two men sat together as friends.

Months later, the Japanese invaded. His call on the radio for Gen. Douglas MacArthur to surrender in February 1942 was taken to task, with the American press calling him a “quisling.” Many other prominent Filipinos participated as members of the Council of State that befriended the Japanese. But it was Aguinaldo who took the brunt in his subsequent trial on charges of treason.

In 1948, with the trial appearing to favor Aguinaldo, President Manuel Roxas ended the matter with the issuance of amnesty. In 1962, he had a last, faint brush with glory when President Diosdado Macapagal moved Independence Day back to June 12. In 1964, the final night of Aguinaldo’s wake was held at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Kawit, from which he had adopted the name of his Magdalo faction in 1896 in the lead-up to the Philippine Revolution. Had he not lived at all, he might as well have been invented as a heroic magnet for controversy.