Heart & soil

Venice, Italy—If your conception of a large-scale architectural showcase was mainly about building, constructing, putting things together, or academic parables about steel and stone, then this pavilion will surprise you. Here, the spotlight falls not on the finished edifice but on what lies beneath: the corpus, the foundation, the living earth from which all architecture draws breath. Such was the quiet power of our visit to the Philippine Pavilion at the 19th International Architecture Exhibition (Biennale Architettura 2025) set in Italy’s luminous, floating city.

The Philippine Pavilion exhibition “Soil-beings (Lamánlupa)”—housed at the Artiglierie in the Arsenale—emerged from a deep collaboration between curator Renan Laru-an and interdisciplinary artist Christian Tenefrancia Illi. The two sought to blur the boundaries between disciplines, departing from traditional exhibition forms to explore how artistic, scientific and architectural practices can intersect around a common material: soil.

Their goal was not to propose solutions, but to challenge foundational ideas of architecture by engaging with the elemental material of construction—soil—as both substance and symbol, matter and metaphor. Instead of designing a static architectural structure, they focused on “perspective, consciousness and relationships.”

The Philippine Pavilion examines soil as matter and metaphor at the Venice Architecture Biennale

“From the start, Christian and I agreed: we didn’t want a didactic or overly intellectual installation,” explained Renan Laru-an. “We wanted something people could feel—something immersive, time-based and grounded in experience. Instead of proposing architectural solutions, we focused on shifting perspectives. The foundation we wanted to transform was consciousness itself—how we relate to land, to each other, to the structures around us.”

The centerpiece of the pavilion is the “Terrarium,” a funnel-reverse pyramid-like structure composed of nearly 1,000 hand-crafted soil tiles made from earth sourced from three geographically and culturally distinct areas in the Philippines: Calatagan, Batangas, an archaeological site with complex histories of colonial land ownership, treasure hunting, and ancestral burial; Baybay, Leyte, a site scarred by recurring landslides, including one during the pandemic that claimed nearly 200 lives, with soil carrying trauma and memory; and Tampakan, South Cotabato, the location of Southeast Asia’s largest open-pit mining project, threatening the ancestral lands of the Blaan people.

Each soil tile contains layers of history and emotion. The red-hued tiles from Baybay embody both geological richness and the grief of communities devastated by disaster. The Calatagan soil speaks to cultural memory. And the soil from Tampakan foreshadows future extraction and loss.

Laru-an stressed, “Each site carries its own layered relationship with the land—from archaeological excavation and colonial histories, to mining and environmental trauma. The aesthetic of soil moves us. We wanted to honor not just its scientific composition, but its emotional and historical presence.”

Christian Tenefrancia Illi pointed out how the pavilion goes beyond the confines of architecture. “What we created isn’t just architecture. It’s a reflection of how communities imagine space. In places where there are no monumental (pieces of) architecture, people gathering on land becomes architecture itself. That’s a radical idea—land as both container and gathering.”

They worked with architects, engineers, and scientists—especially the Natural Building Lab at Technische Universität Berlin, where they tested water impact on the tiles. Soil samples were also sent to University of the Philippines Los Baños, Visayas State University, and the Bureau of Soils and Water Management.”

Laru-an went on to say that in places like Calatagan, you see how colonial ownership, tourism and archaeology all intersect. “Land there is both sacred and exploited. In Tampakan the soil represents a future that’s already being carved out by mining interests. There’s trauma in that too. We didn’t want to showcase soil just as scientific data. It has its own aesthetics and agency. It holds emotional and political weight.”

Illi observed how architecture has become so disconnected from land. “Modern urban planning doesn’t consider soil as a living, intelligent system. But soil contains multitudes—millions of biological organisms in a handful. It’s not just the foundation. It’s life.”

Laru-an nodded in agreement. “This project isn’t just an installation; it’s a conversation starter. It’s about community, memory and rebuilding. In many ways, it’s about returning home.”

Victorino Mapa Manalo, chair of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), remarked, “I am proud to witness how this pavilion, which was once just an idea, has grown into a space that brings together soil architecture and cultural meaning.” Credit goes to how the NCCA’s Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale (PAVB) team was able to give flesh, provide shape to this, pun intended, groundbreaking concept.

Manalo continued, “This is an exhibition literally grounded not only in physical material, but in collaboration, research and care. We see almost a thousand tiles of soil, each one carrying the story of a place, a community, a climate. Together they create a map of relationships between architecture, ecology and culture.”

It reminded Manalo of a time in his younger days when he witnessed a house being built in an unusual way. Instead of laying bricks one by one, the builders shaped the entire structure out of clay. Once it was complete, they covered it with coals and baked it whole. Curious, he asked the architect why they spent so much time working with the clay. The architect replied, “Because the soil is a goddess.”

Manalo concluded, “You might want to ask yourself, how is this (exhibition) architecture? And it really is, because you’re working with the building block of the structures that surround us. Soil carries memory, shapes and landscapes. It connects us across time and place.”

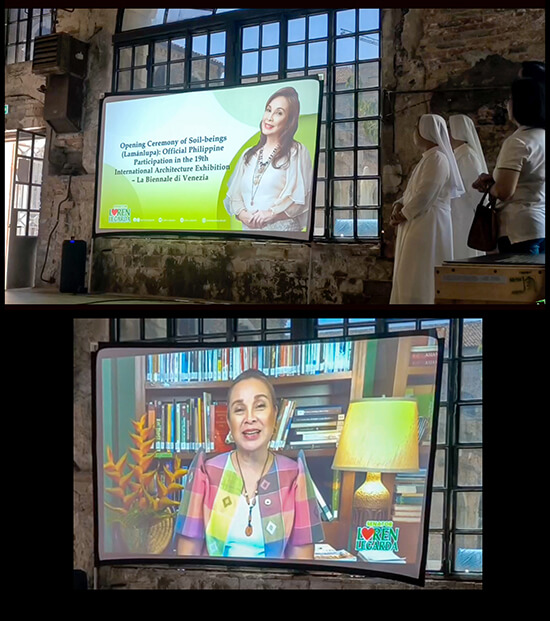

Yet for too long, architecture has treated soil as a mute foundation—something to be mastered, built over, or extracted from; this pavilion insists otherwise,” explained Senator Loren Legarda in her video speech during the opening of “Soil-beings (Lamánlupa)” at the Arsenale. “Here, soil is a teacher, guiding us into dialogue with the earth, with time and with one another.

Senator Legarda is the visionary and principal proponent of the Philippines’ re-entry and ongoing participation in both the Venice Art and Architecture Biennales. The senator sees this as a vital act of nationhood: a way for the Philippines to plant its creative vision firmly in the world’s consciousness, cultivating understanding and respect through art and architecture.

“‘Soil-beings’ was shaped through community workshops across Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, where farmers, Lumad elders, scientists, youth, and artists bridged the technical and the ancestral. And what forms emerge—soils from across our archipelago, arranged like a gathering of elders. They whisper of erosion and renewal, breathe humidity and storm, and reject the illusion of permanence. Architecture here is not a monument but a movement, a reverence for the living Earth.”

Soil Immaculate

It’s interesting how the structure was designed to break down, from soil to something else. It’s irrigated, and as water flows, the tiles erode. It was intentional. It reflects erosion, migration, transformation, and new topographies. What happens when land is worked, lived on, or abandoned. It brings forth images of open-pit mining, rice terraces, and even cemeteries. These are all human interventions in land, and they carry the imprint of labor, memory and temporality.

“It also speaks to our diaspora,” insisted Laru-an. “Soil moves, like people do. It changes shape and meaning depending on where it goes and who carries it. Eventually, the soil may be returned to the Philippines—altered, but still connected.”

While other pavilions present solutions (new models, futuristic designs) the people behind the Philippine Pavilion had gone the opposite route. Laru-an mused, “Instead of proposing something to build, we wanted to reframe the conversation: What do we mean by building? By architecture?”

Maybe this will all remind us that architecture is not only what we build, but also what we choose to remember, protect, and let go.

Interestingly, the opening of the PH Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was attended by overseas Filipino workers based in Venice, Milan, Padova, and Treviso, among other cities. Those who have bravely uprooted themselves from the homeland to seek better lives, building their own homes, their own terra in Italia. Imagine their response, standing within these centuries-old walls, suddenly face to face with pieces of the Philippines—fragments of home, reassembled and revered on the world stage.

The soil remembers; land, indeed, is a living archive.

As Senator Legarda cited in her speech, “For in the end, we are not separate from the land. We are—each of us—lamán ng lupa.”

* * *

The Philippine participation in the Venice Architecture Biennale is a collective and collaborative undertaking of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, the Department of Foreign Affairs, and the Office of Senator Lauren Legarda. It continues to reflect the country’s commitment to artistic excellence, environmental sensitivity, and meaningful international engagement.