36 hours in Antique: In the place of small rivers

Antique, that long sliver carved out of the west coast of the island of Panay, contains all the glorious DNA of our country’s history, its sorrows and tragedies but also its legends and glorious triumphs.

Its mountains, so closely bound to the sea, together create the idea of an implacable, all-powerful nature. Indeed, Antique, then as now, is a roughhewn paradise, that must have dearly perplexed the first Spanish friars who landed in Antique to seek souls and bring them to Christianity in 1581. It still is full of strange flora and fauna that give the places their picturesque names—the plump, placid ants called hamtik, the spiny ongon thorn, and the valley of the anini or the place of small rivers.

Today, that same untamed wilderness has the breakout potential for a Gen Z refuge and the unmistakable appeal of the new adventure traveler —the kind who likes to trek up to view a sunrise from a different peak every day of the week. Antique has plenty of these mountaintops and some of them are the highest in the country.

It’s the less-traveled destination of the West Visayas, although it’s an easily accessible 2.5 hours away from Iloilo City through superb roads. There are two routes to reach it: the first, by a well-built avenue that follows the coastline, and another, up a winding road, shored up by riverstones, through the mountains, that has the air of Kennon Road.

Antique, in fact, is to Iloilo what Sagada is to Baguio City. The province even has its own rice terraces nestled in the hills. It is, however, entirely unblemished by roadside signs or softdrink or telco ads. It has a basic agricultural economy in sugar cane and cacao, some rice and coconuts.

There is a coastline that features a sea that rages to the very edge of the fishing villages. There are no breakwaters to cut the fury of the waters.

This kind of unforgiving terrain is not surprisingly peopled by heroes, led by Gen. Leandro Fullon and his officers who waged an effective guerrilla war against the Spanish and the Yanks.

Make no mistake, it also has plenty of creature comforts, including two stylish hotels (the Xela and its sister, The Pinnacle) in the capital of San Jose. The food is excellent, and if you were in Manila, would go by the name “artisanal” with all the right buzzwords such as single-origin, wholesome and authentic. (Think seedless avocados, pink and purple yams, black rice and hearty thick soups.)

Two of its most important colonial structures are the Casa Tribunal de Patnongon and the stone church of San Jose de Nepomuceno in Anini-y.

There are records that prove for certain that the Casa Tribunal was built with the blood, sweat and tears of the notorious polo y servicios—which obliged all able-bodied Filipino men from 16 to 60 to serve in the building corps of the Spanish colonial government, digging ditches and paving roads but also constructing the grandoise structures we still see today, the churches and government houses and in this case, the “hall of justice.”

The principalia (or leading indio families) were exempted from many of the taxes, but would still have to pay their way out of the yearly polo, which amounted to 40 days’ unsalaried service in each year.

In very real terms, these places—the Casa and the gorgeous Anini-y Church—truly belong to the people, the Filipinos who broke their backs raising them.

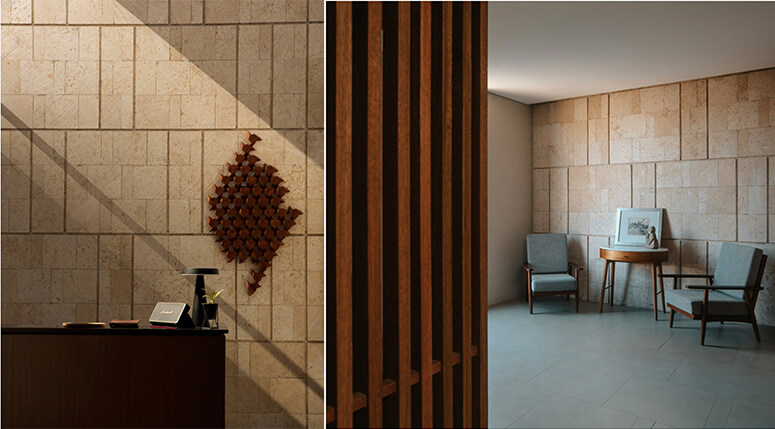

The Casa Tribunal, first erected in the 17th century, began as a simple affair of bamboo thatched with palms. It would later morph into a two-story structure made of cream-colored sandstone— quarried from the mountains of Antique.

That it’s the only one of its kind still standing—or perhaps even built—indicates that Antique had few of the resources, including the manpower, to create more.

The Casa, a combination of Yorme’s offices, the DOJ and NBI prisons, would fulfill its duty until World War II when it was finally taken over by the Japanese Imperial Army who made it into a garrison and a tokhang-chamber for resistance fighters.

Antique proved so hard to govern, however, by the Japanese that they managed to command only a handful of the province’s towns. Possibly in retaliation, its marauding forces razed the Casa to the ground. For nearly 80 years, it stood as a crumbling relic of those days—the good, the bad and the terrible—on Calle Real.

Only its walls remained standing; its wooden floors and roof, glass windows were all gone. Until in 2023, the stars aligned and a near-miracle happened: Senator Loren Legarda led the campaign to allocate enough funds to the National Historical Commission to breathe new life into the hollowed-out landmark.

“Heritage is about clarity. When we understand where we come from—what we built, what we lost, what we survived—we begin to understand who we are,” Legarda said. “And that understanding is vital to how we move forward,” she explained.

It was a tall order at first to recover this lost past since the Casa’s original plans had also gone up in smoke in World War II. The Commission’s historic preservation department adapted the drawings of other casas in other parts of the country to piece together its reconstruction.

“Our origin stories are important,” Legarda declared on the day of the turnover of not just one but two restored structures on the same day last week.

The church of Anini-y is named after a medieval priest who was drowned in the river of Prague—yes, the same town of our beloved Sto. Niño—for refusing to share the secrets of the confessional with the king. It’s a majestic sight, laced with elegant stonework that is a wonderful case of a cathedral interrupted.

By 1896, only three of its walls had been plastered over. Its western wall and the wall behind the altar still stood bare, the smooth round stones, gathered from riverbeds, uncovered. It seems the indio workers had apparently thrown down their tools to join the Philippine Revolution and the Spanish parish priest would flee from the Americans a few years later. The restoration is mindful to keep it just as it looked more than 120 years ago, an important reminder of how fortunes and history can go awry.

There were other activities in the 36 hours spent in Antique which included a tour of the newly-opened outpost of the National Museum (featuring an exhibition titled “Paghabul sa Antique” of woven delights).

A second cultural space at the repurposed town hall was a showcase of local crafts—turmeric and ginger teas, silk sarongs and mules, bamboo bags, candied peanuts, and pretty jackets with terno butterfly sleeves, hemp espadrilles, shell trinkets and jewelry.

Finally, to add to the air of a story that still needed to be written, upstairs, a poetry book by National Artist Rio Almario in two languages was launched.

“Let this be our promise,” reminded Senator Legarda, “that long after we are gone, our children—your children—will still walk into this place, feel its history, and know they belong to something greater.”

In such ways—through stone and fabric, song and poetry—does the Filipino identity set sail.