Pinoy poets in Persepolis

Fourteen years make for deep enough memory. But geopolitical events that recently gripped global attention revived milestone moments when fellow poet Ricardo M. de Ungria and I found ourselves touring the ruins of Persepolis in October of 2011.

As the USA followed up Israel’s aerial bombardment with haymakers that included bunker busters, CNN’s map of Iran showing suspected nuclear development sites had me on empathetic tenterhooks. One of these sites was Estakhr, which I recalled to be proximate to Persepolis—14 kilometers away, in fact.

I hoped that Trump wouldn’t be compared to Alexander the Great, who turned the historic ceremonial capital into ruins in 330 BC. Thank the skies for the skills of MAGA’s Air Force; the ruins that are a UNESCO World Heritage Site avoided a state of smithereens.

Thanks to translator and interpreter Dr. B Samadi of the Cultural Office of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Manila, Ricky and I were invited to the Second Congress of Iranian and International Poets from Oct. 8 to 14, 2011, on a generous stipend. The flags of over 40 countries were arrayed in front of the Laleh International Hotel in Tehran, where the visiting poets were billeted. Young Iranians composed the secretariat at the lobby.

On a free day, we wandered about Lahle Park nearby, on our own. Later, we were told that we had to notify the secretariat before conducting such freeform activities. The organizers were intent on providing strict security for all guests all the time.

Deputy Chief of Mission and Charge d’Affaires Mariano Dumia of our embassy in Tehran showed up. A history professor, he regaled us with a broad-strokes chronology of momentous affairs and shifts in geographical boundaries in the region. He also hosted a welcome dinner at the elegant Shandiz restaurant, where we savored mai-ichi or skewered lamb chops and sislik or slow-baked leg of lamb, among other delights.

Interviewed for video, Ric and I recited a poem each in taping sessions conducted at the hotel lobby. The hectic schedule started with a walking tour towards the Carpet Museum.

At Vahdat Hall, where the inauguration ceremony was held, stand-up tarpaulins honored each attending poet with excerpts from his/her poetry. We were told that the congress had been arranged with the aims of exchanging views and helping to promote justice, peace, and friendship. Yhya Talebian, deputy minister of culture for poetry and literature, then expressed the hope that the foreign participants would help transmit the reality of Persian literature to their countries. Over the next two days, we read our poems at three universities and at the House of Artists, an excellent fine arts complex that had Waiting for Godot being staged in Parsi in one of its theaters. Fate had me reengaging with old poet-friends Ebrahim M. Wa Bofelo of South Africa and Abdul Wahib of Indonesia.

We were flown from Tehran to Shiraz in the southern part of Iran. Our mystical tour became even more magical, with stops at poets’ shrines and mausoleums, the Shiraz University, and the Vakil Complex and Bazaar.

At Hafezieh or the Hafez Mausoleum and Gardens, we saw how poetry draws so much reverence, a legacy from ancient Persia. Shrines for notable poets are kept attractive with surrounding gardens welcoming a constant stream of visitors. Oct. 12 happened to be Hafez Day, too. We also visited Sa’adi’s Mausoleum. Shrines for other much-loved poets, such as Ferdowsi, Rumi, and Omar Khayyam, were probably in other cities.

After four nights in Tehran and a couple in Shiraz, we finally boarded a bus for the hour’s drive to Persepolis—bragging rights to history. Here was where, in 1971, the then Shah of Iran hosted a grand global party that included Imelda Marcos as a guest, for the 2,500-year celebration of Iran’s monarchy, which fell eight years later.

Persepolis was established by Darius the First when Persia ruled half the world, around 500 BCE. It was the King of Kings’ predecessor, Cyrus the Great, who had chosen the site. Darius began the construction of the dual stairway, now known as the Persepolitan Stairway, as well as the vast terrace, palaces, and the Hall of a Hundred Columns. Other notable structures were completed during the reign of his son Xerxes the Great, such as The Gate of All Nations.

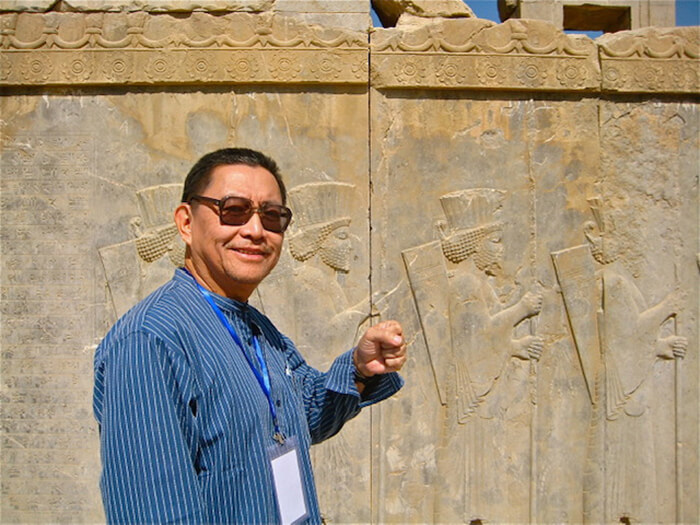

Some of these ruins were still partly in place, starting with the formidable stairways and the half-broken Gate of Nations. Among the close-up photos Ricky and I took were of limestone carvings of Zoroastrian symbols and images, as of the familiar lion, representing the sun, in perennial battle with the bull, representing the earth.

Historians opine that Alexander had taken vengeance for the earlier destruction of Greek temples by the Persians. And it is amid a cycle of ruins that poets may now glimpse resplendence of a sort—maybe in the aridity of the moment, or the sight of a white Monobloc chair propped up against a fallen column.

I’m not sure if Ricky ever wrote a poem about climbing up a hill towards the sepulchers of kings. For some reason, I never did get to finish one I started. But I just found some notes, or what seems to be an initial draft. Maybe it’s time, after 14 years, to revise and complete it to my satisfaction:

“Something about all that space, created/ in the middle of nothing, sparks the first notion/ of heightened language. Not just a description of sheer landscape,/ no matter how extraordinary./ It has to reflect on the human situation,/ or a heart all too human.// Our sensors turn as sharp as the sun./ We see, hear, smell, and taste spectacle, so distant/ as to have been subject to periods, epochs, eras.// Whenever we’re confronted by expanse,/ under clear blue sky, it isa mortal foible

to think we are insignificant./ We are stepping into place, upon old ground./ No sweat ever forms on our brows./ Our imagination is soaked in recall and reinvention.”