Reimagining spaces for learning: The story of Bagong Silang Community Library

The education system is in crisis: this is the prevailing narrative that is popular today.

It is not an arbitrary claim that people utter, but one experienced at the grassroots level. It is enforced with statistics provided by research and personal experiences of students, parents, teachers, and other stakeholders. However, there is an emphasis on the crisis in literacy and critical thinking, since both are crucial for personal growth and cognitive development.

With the current crisis that the education sector is experiencing, many efforts and attempts are being made by groups and individuals to address and respond to the issue. One attempt is the existence of community libraries. The Bagong Silang Community Library is an example.

The crisis in education can be viewed through various lenses. One approach to understanding this crisis is how it affects the students in terms of literacy and reading comprehension. Another is its implications for students’ reasoning skills and critical thinking.

The challenges faced by students during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the economic divide in different socioeconomic classes. Students lack the resources for adapting immediate shift in learning, and this is also the case with children in Bagong Silang, Caloocan City. Some were forced to stop their studies since they could not adapt to sudden changes. The result is that they were left behind.

My younger brother, who was then a Grade 3 student, had difficulty reading simple Tagalog words and sentences. It was a concerning observation since, despite the learning crisis occurring prior to the pandemic, students should be able to read at least during their formative years. What is more unsettling is the fact that it was not an isolated case. Most of his friends, who were the same age and grade level, had this challenge. It was then that we decided to put his books at the front of our house where they play to encourage their interest in reading.

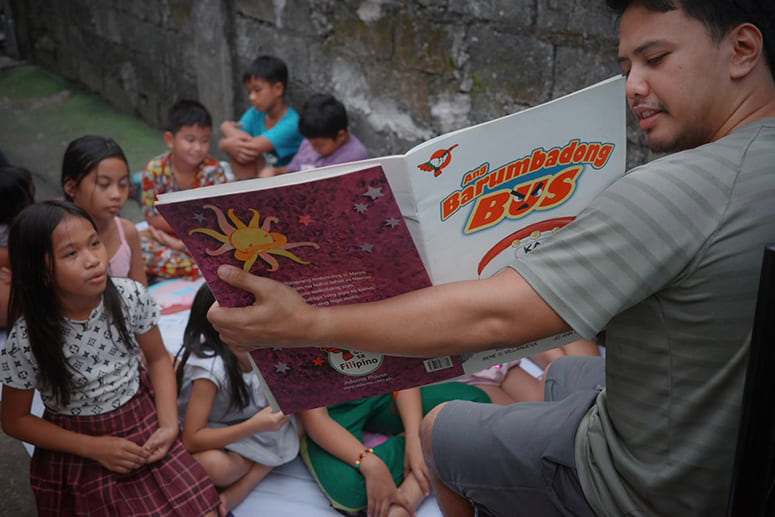

Surprisingly, the children were curious and perplexed about the books. One of them noticed that it was not the same as their textbooks in school. I consider that event as an encounter with a whole different culture, which opens a way to engage them with reading, mediated by used, old, and dusty books. Since the response was positive, I conducted a storytelling session. We repeated the session a week later, and we called it, “Libreng Basa, Libreng Tinapay.”

The role of tinapay is important. It allows us to connect with children and encourage them to be involved in reading. And as someone living in Bagong Silang, this is hitting two birds with one stone. The bread is distributed, not based on the level of participation or the number of correct answers, but equally as a reward for being involved in the storytelling activity. It is our way of countering the culture that learning should be punitive and hierarchical based on grades. We promote motivation-based reinforcement and a non-hierarchical attitude. Once the storytelling is done, everyone will get bread.

To be able to read is one thing. To ask difficult questions is another. We are trying to provide space for fostering both.

If there is a thinker who had a huge influence on the creation of the Bagong Silang Community Library, it would be the Brazilian philosopher and educator Paulo Freire. For Freire, reading a word is connected with reading the world. Thus, we recognize the potential of stories to understand immediate reality.

The donated books include stories that discuss various important topics that incorporate virtues and concepts like courage, honesty, friendship, fairness, temperance, and others. In encountering these stories and virtues, we come to encounter different ways of grasping the world. It expands children’s horizons of creative imagination and sparks curiosity, the phenomenon of being alive.

In line with the quest for understanding the existential experience, we started the Pilosopiyang Pambata, a series of sessions on everyday philosophical questions. To be able to read is one thing. To ask difficult questions is another. We are trying to provide space for fostering both.

Another goal of the Bagong Silang Community Library is to involve other people. Groups like The Happy Ripples and ISIP Pinas transformed how we do our reading sessions. Other communities in Cebu, Iloilo, Rizal, Pasig, and Kidapawan were able to establish their own community libraries. However, there is no single form or shape of the space for reading. It is customized based on the needs and capacity of the community. It varies depending on the challenges the communities are facing.

The question we face now is what the future will look like for our community library. What we aspire to is to become obsolete, recognizing that efforts like this by the community should not be permanent. These initiatives shall only be an immediate response and not a long-term solution. But as long as the crisis prevails, there will be a necessity for it to continue.

Hence, we are demanding accountability from those responsible for its existence. Community libraries are symptoms of the illness that the education sector is experiencing. Our call is a reimagination of spaces for learning outside schools: a space like public libraries that provide access to books, programs that cultivate a habit of reading, and avenues to promote literacy and critical thinking. The government has an obligation to fulfill these demands. Once public libraries are available, community libraries will be redundant. Then our goal will finally be achieved.