Youthful (re)imaginations of social change beyond elections

Often framed as symbols of hope, the youth are burdened with the unquestioned yet loudly spoken responsibility to transform society. Especially during elections, we are expected to participate actively and vote wisely, as if our vote could undo or radically change everything that has been built before us.

But what if there's too much hope yet little room to act? And when we're trying to act, the only viable option given is merely shading the ballot?

These are the reflections that shaped the core of Tara Kabataan.

We are a youth-led collective based in Manila, an offshoot of the 2022 Kakampink movement. Formerly known as the Youth Vote for Leni-Kiko Manila, we've transitioned from organizing partisan sorties and house-to-house electoral campaigns to co-organizing community-based initiatives and human rights advocacy campaigns.

Our reformation did not happen overnight. But it did start on the night of election day, when our volunteers started processing the results after pouring their hearts into volunteering.

While some were in tears and the others were losing hope, one question echoed loudly across the room: What's next?

And so, we started to reimagine beyond the ballot.

It took several months, and we’re still figuring things out. Trying, failing, and moving forward have become part of our collective life.

So, over the past years, Tara Kabataan has been a shared space for the youth from all walks of life. So diverse that each of us holds a different definition of what and who we are. It could be a home, a community, a movement builder, or something else entirely. But perhaps it is our ability and inability to be all these things at once that define who we are.

We found ourselves responding to man-made disasters and extreme weather events like fires and typhoons. One of our most visible efforts was disaster response. We help in relief operations and augment the support by focusing on young children often left out in the distribution of sacks of rice and canned goods.

While doing this, we encounter diverse stories, realities on the ground.

I recall during our post-event processing, a child drew the Department of Social Welfare and Development, and along with their peers, shared that they were scared of being relocated or taken in by someone else after the fire. And for us, the question remains: How do we respond to that?

Psychosocial support program.jpg)

Since then, we’ve tried to face head-on not just the urgent, but also the structural, difficult, and uncomfortable problems—the kind of problems that are impossible to resolve overnight.

How can we seek justice for the impacts of climate change? What do we do for and with victim-survivors of violence? How can we institutionalize gender equality and labor rights?

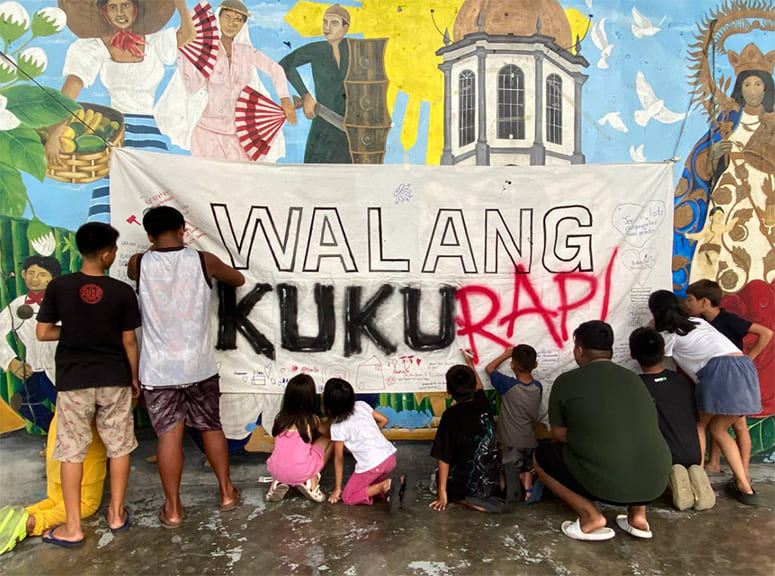

To face these realities, we’ve held on to three core values that guide us in our work and relationships: pakikipagkapwa, kalinangan, and ginhawa. These are values that we live in every day, within formal meetings, rap exhibitions at barangay basketball courts, or watching human rights films in local public libraries.

We’ve learned that, unlike electoral campaigns which are time-bound and often flashy, community organizing demands a more meaningful yet slower pace, cherishing every relationship built along the way.

Our shared history is built on the phrase, “Angat buhay lahat.” And maybe that’s one of our integral inspirations: that everything we do must lead somewhere, and that destination is ginhawa—the well-being of our bayan, our people, our communities, including ourselves.

While it’s true that the medical missions we organize bring relief, we recognize that these needs are rooted in the systemic lack of health support. These are not issues that elections can solve alone, as they require sustained collective action.

Unlike electoral campaigns, which are time-bound and often flashy, community organizing demands a more meaningful yet slower pace.

Still, we are constantly reimagining even the way we act. Helping others is not just about the other. It is also an act of helping the self. It is a critical process of learning, unlearning, and transformation.

Advocacy work does not mean separating the self from others but rather rests on enjoining, transforming, and growing together.

To us, transformation often flourishes in unfamiliar contexts. Sometimes joyful, sometimes painful. Regardless, always generative.

Through this transformation, we recognize multiple ways of knowing and empowerment. Beyond formal settings, dominant languages, or traditional norms.

For me personally, it is about being open and vulnerable to others. To some of my friends, it is about listening and stepping back.

Ultimately, kalinangan returns to where it must begin: in solidarity with others in principle and through action.

It reminds us that in campaigns for equality, we must also begin with how we relate to one another. We can’t preach something we can’t do to our circles and ourselves.

And it must always be grounded in human rights and dignity.

Last June, we organized and celebrated our first Pride event in Tondo. Reactions from onlookers were mixed. As we walked past basketball courts and wet markets, we could feel the contrast between joyful spectators and the skeptical eyes of some community members.

Community Pride Parade.jpg)

I would say it was a success. It was an event that introduced our advocacy despite differences. It was also about being seen and knowing that even if people understood you differently, you could still be heard.

And maybe that in itself is a step forward. To reimagine how we define “success” for our youth collectives. We are often evaluated by ballots, certificates, conventions, awards, or ranks that reinforce hierarchy more than empowerment.

But perhaps part of reimagining is also understanding why those metrics exist and how we can dismantle and rebuild differently.

This July marks Tara Kabataan’s third anniversary—three years of shared failure, growth, and dreaming.

Whenever we talk about how we began by losing, we also affirm how far we’ve come. How we are still here and still continue to persist.

It is the reimagining of our 2022 “loss” that allowed us to hope. It inspired us to look beyond without turning away from what is. It is a kind of learning through discomfort and a practice of care amid hardship.

To my fellow youth, what I want to say is this: what we most need today is a (re)imagination of the self and our communities.

Not a kind of airy-fairy daydreaming but a grounded, rooted act from our shared experience.

As we always say in Tara Kabataan, hindi natin kakayanin na tayo lang. Kasama natin ang kapwa tungo sa ginhawa.