Ano’ng say mo?

Because August is Buwan ng Wikang Pambansa (National Language Month)—a month-long observance institutionalized by Proklamasyon Blg. 1041 (s. 1997), which expanded the old Linggo ng Wika (language week) into a full month—I’ll be talking about our mother tongue, in our unofficial tongue from another mother.

When I was in grade school, we marked Linggo ng Wika with poster-making contests, essay-writing competitions (which I loved), and a costume parade (which I totally hated). We looked like miniature cosplayers in our Barong Tagalog, baro’t saya, terno, farmer’s outfit, or some indigenous people’s traditional garb, coupled with DIY headdresses and accessories.

It was uncomfortable as hell, and the only thing that kept me going was the thought that I was neither alone nor the last to go through this annual hazing. Sometimes, the heavens even conspired and brought in a typhoon just in time to literally spoil the parade.

Except for hashtag challenges and online popularity based on the number of Likes on social media, not much has changed in this tradition. But the real debate around this time isn’t about who wore it best, but whether Filipino, Tagalog, Taglish, or emoji best expresses true patriotism. After all, the celebration highlights not only Filipino, but also the country’s other languages.

Sidebar: Efforts toward a national language date back to the 1930s, when the Institute of National Language recommended Tagalog as the basis of instruction in schools. Linggo ng Wika is celebrated in August partly to honor President Manuel L. Quezon, born on Aug. 19, 1878, who championed the development of a national language during the Commonwealth era. By 1959, Tagalog gave way to Pilipino, then to Filipino under the 1987 Constitution.

For decades, Philippine public schools survived on a tried-and-tested bilingual diet of Filipino and English, with the occasional curriculum shake-up to keep everyone guessing. Then came 2012’s Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE), aimed at accelerating learning by utilizing the language that kids first used at home.

The ‘Taglish is bastardized English’ debate lingers like a stubborn ingrown.

However, the country’s linguistic buffet made for MTB-MLE’s messy implementation: teachers scrambling for training, textbooks getting swapped midyear, and children staring blankly when the “assigned mother tongue” sounded as foreign as High Valyrian.

Fast forward to last year’s Republic Act No. 12027, which restored Filipino and English as the primary classroom languages, with the mother tongue downgraded to “optional.” Starting with AY 2025–2026, DepEd is officially back to basics, with regional languages politely relegated to supporting roles.

It’s hard to imagine why there’s even a debate about this. In the old days, English was English, and Tagalog was Tagalog. Our lolos sounded like retired voice talents from those grainy B&W war documentaries, while our lolas and titas corrected our grammar at every opportunity, à la Stannis Baratheon enlightening Ser Davos Seaworth on when to use “fewer” instead of “less.” In turn, Ser Davos passed on the knowledge to Jon Snow, who could finally boast knowing something.

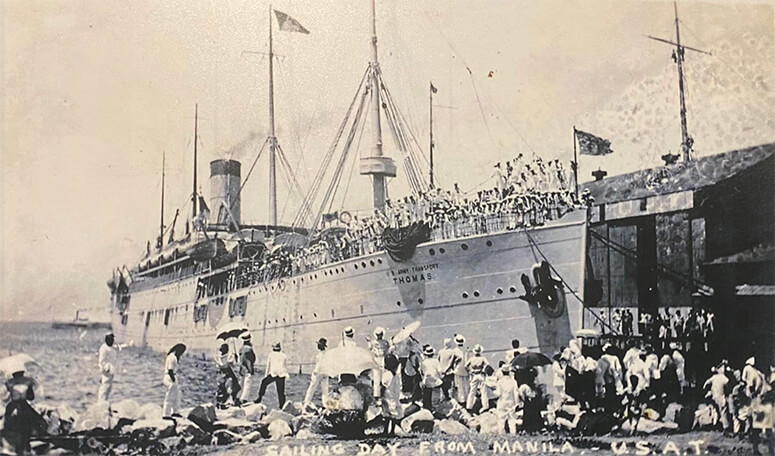

For using English properly as a second language, our forebears had the Thomasites to thank (or blame). On Aug. 21, 1901, some 500-plus American teachers arrived in the Manila port aboard the USAT Thomas. Their mission—which they obviously accepted—was to establish a nationwide public school system across the archipelago, train Filipino teachers and, most importantly, use English as medium of instruction, supplanting the Spanish-era school network. Their work helped make the Philippines one of the world’s largest English-using societies in the 20th century. In hindsight, without such linguistic annihilation, we could have concurrently become one of the largest Spanish speakers outside of Spain.

In the old days, being able to write and speak in crisp, grammatically impeccable English was a badge of intellectual elitism—and I suppose it still is—according to its user status, class, and desirability, both in employment and in romance.

Was dropping the mandatory mother tongue a good idea?

In classrooms where five “first languages” jostle for airtime, the answer is probably yes. With the focus having shifted back to Filipino and English, teachers no longer need to moonlight as virtual UN interpreters.

That said, the policy still allows mother-tongue instruction in genuine monolingual settings, while the rest rely on auxiliary language support— assuming there’s a teacher who knows when to deploy it. Critics worry about cultural erosion, while some communities have gone as far as challenging the law in court.

Meanwhile, the “Taglish is bastardized English” debate lingers like a stubborn ingrown. Some experts, like Dr. Maria Lourdes S. Bautista, have argued that it’s less bastardization than brilliance, more a rule-bound, nuanced dance between two languages, often wielded by those who are fluent enough to pull it off with style.

Does the Queen of All Media—she who made Taglish conventional for younger generations—agree or disagree?

And does speaking less-than-pure Tagalog make one unpatriotic? I think not. After all, patriotism lies in our anthem, our flag, our love for lumpia and adobo, and our ability to cheer “Laban, Pilipinas!” in both Tagalog and English (and even if our contestant loses).

In this generation of TikTok and AI dependence, it is no longer just advisable but imperative to acquire language skills early, to make it neat and orderly like a Tokyo subway queue, not like Metro Manila’s traffic. Well-meaning government policies can’t simply dictate which linguistic tools kids should get before the UI (that’s “user interface” for all you tech dinosaurs still pretending floppy disks might make a comeback like vinyl) of adulthood locks in. Evidently, flawless and consistent implementation is the key to success.

As Bill Murray’s Bob explained to Scarlett Johansson’s Charlotte in Lost in Translation: “The more you know who you are, and what you want, the less you let things upset you.”

Apply that to language and you’ll realize that fluency isn’t just about grammar or vocabulary, but rather about effective communication and expressing yourself with clarity. When you know who you are and what you want to say, language becomes a bridge, not a barrier.