Coke Bolipata on living lives beyond performing

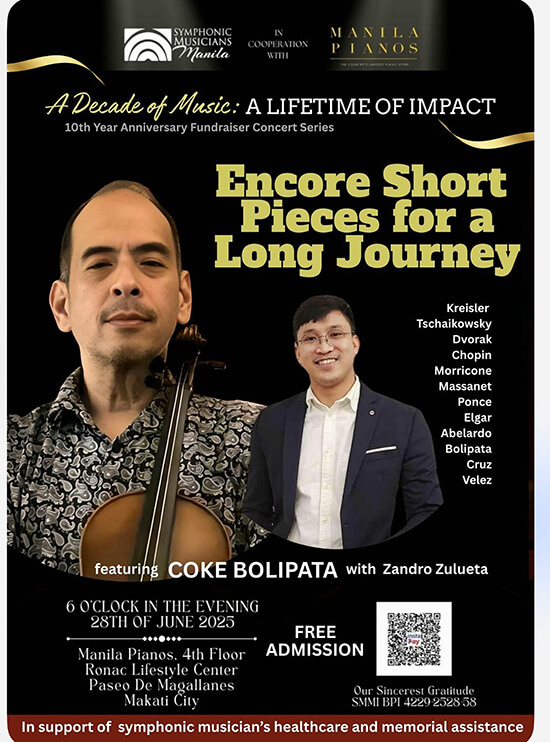

When violinist Alfonso “Coke” Bolipata performs at the Manila Pianos Saturday, June 28 at 6 p.m. with pianist Sandro Zulueta, he will have completed a full cycle as artist and music mentor and festival administrator of the now unique Pundaquit Arts Festival in San Antonio, Zambales.

The recital of short Kreisler, Dvorak, Chopin Massenet and on to Nicanor Abelardo’s Cavatina and his very own Song of the Mermaid is really his first in a decade.

He told The Philippine STAR: “This isn’t a repertoire that comes most naturally to me—not because it lacks difficulty, but because it demands a different kind of artistry. The challenge lies in evoking the zeitgeist of a bygone era—one not only lost to time, but also, in many ways, to place. These pieces require a particular spirit, a kind of joie de vivre, a lightness and spontaneity that today’s world no longer readily offers.”

He notes that the program was really known as salon music that never took itself too seriously. “It has brief emotional arcs that begin and end without grandeur, no sweeping narrative to carry you through exposition, turbulence, and catharsis. In this sense, the long-form works are more forgiving. They allow room for dialogue—with the material, with the audience. Short pieces afford no such space. The music must arrive fully formed—complete, self-contained, and often, paradoxically, more demanding. What is spare must feel abundant; what takes great effort must seem entirely effortless. This is the paradox—and the poetry—of these encore works.”

The ones that feel closest to home are the ones he has been playing since he was seven or eight. “These are Méditation, the Kreisler pieces, Songs My Mother Taught Me. And of course, the Filipino works always feel the most familiar, the most instinctive. They engage Filipino audiences with ease—as if telling them a story they already know by heart.”

I’ve come to understand that playing the violin isn’t just about sound. It’s about memory, legacy, and learning to speak through something that was once given in place of words.

While he had originally planned to perform Ysaÿe’s Ballade, Chausson’s Poème, and Franck’s Sonata for a full French program, the producers wisely chose a lighter repertoire for this occasion. “For me. what matters most is why we play.”

The concert is dedicated to the PPO harpist-pianist Lourdes de Leon Gregorio whom he considers his long-time collaborator, rehearsal pianist, and a quiet force in the lives of so many Filipino musicians. “She was with me for the ‘Pelikula’ album and, in the 1980s, played harp for my performances of Chausson’s Poème and Ravel’s Tzigane with the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra. She has been my rehearsal pianist for Mozart, Bruch, Saint-Saëns, Brahms, Bartok, Beethoven, Berg, and Prokofiev concertos. Her contribution to our shared musical journey is immeasurable. May she continue to live a long and meaningful life. This music is offered as a quiet tribute to the depth, grace, and generosity she has given so many of us.”

His natural turf is chamber music. “My musical arc has always found its most natural expression in chamber music—perhaps because of my lifelong collaboration with my brothers, or a certain instinct for the lyrical and the long arc. I’ve always been drawn to music that unfolds slowly, that rewards patience and deep listening. There’s a kind of complexity in it that I love, almost like solving a riddle—not in the cerebral sense, but in the way something intricate and delicate gradually reveals its logic. These salon pieces, though seemingly simple, ask for the same sensitivity. And so, even in unfamiliar terrain, there’s something familiar: the search for shape, breath, and meaning within the smallest turn of phrase.”

It was teaching young people and organizing festivals that, to him, were more rewarding.

Indeed, he was privileged to be mentored by Maestro Oscar Yatco and nurtured within the confines of the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra. “These were formative years, grounding me in the canon while also affirming that such a path was possible, even here. And yet, it was Casa San Miguel that altered my trajectory. It saved me from the rigid linearity of a conventional performance career and opened lateral directions — paths that allowed me to explore other urges: teaching, curating, organizing, creating space for others. The violin never left my hands, but the role it played expanded. It became not only a tool for solo expression, but also for community building, for storytelling, for asking deeper questions about art, identity and place.”

More recently, that journey has taken the shape of writing. “What began as a personal reckoning—an attempt to make sense of memory, loss, and the cultural silences I grew up with—has grown into a body of short fiction. Like music, writing is another form of listening: to voices that weren’t always heard, to stories handed down in fragments. And like the violin, the act of writing requires precision, vulnerability, and the willingness to hold silence as much as sound. The violin may have led me to the world, but writing brought me inward.”

He points out his life as a teacher and festival organizer has been a continual weaving of art, purpose, and community. “Teaching, for me, has never been just about instruction—it’s about nurturing imagination, discipline and voice. Whether guiding a young violinist through their first notes or mentoring an artist in shaping their narrative, the work is always grounded in awakening a sense of agency and wonder. Festival work began as a natural extension of this—initially focused on staging concerts and creating spaces for performance. But over time, it evolved into something far deeper: a platform for education, critical reflection, and cultural reclamation. Festivals like Pundaquit became more than events — they became vessels for memory, ecology, storytelling, and local empowerment. Programs like Zambulat expanded this vision, embedding artistic practice within community engagement, heritage work, and environmental consciousness.”

The Casa Pundaquit school has been a vital part of Coke’s journey. What began as a modest program in San Antonio has since expanded, with satellite sites now in Tondo and Batangas. “Our core community has grown to over 200 young learners each year, many of whom return annually, forming a living, evolving family. And with the launch of our teacher training program, we’ve experienced a massive leap—scaling up to reach over 2,000 students through public school partnerships, equipping teachers to integrate arts and cultural literacy into their classrooms.”

Indeed, teaching and organizing have become inseparable. “They are about building something that lasts beyond a single performance or lesson: a sense of continuity, of cultural rootedness, of possibility. And ultimately, about creating spaces where art is not a luxury, but a way of life.”

At first, the thrill of organizing festivals centered on bringing artists and audiences together—the sheer joy of performance, of staging something beautiful, of creating a moment. “But over time, I realized that events, however dazzling, are fleeting unless they’re rooted in something deeper. That’s when the work began to evolve—from simply mounting concerts or exhibitions to building a more enduring framework: one that involves education, research, curation, and, most importantly, context. A festival should do more than entertain—it should ask questions, inspire dialogue, and connect communities to their own cultural narratives. That’s what led to programs like Zambulat, which is as much about community empowerment as it is about art. It brings together artists, teachers, students, and local stakeholders to co-create meaning around shared histories, forgotten stories, and ecological urgencies.”

As a mentor, he finds fulfillment totally different. “It’s not just in the applause after a concert, but in watching a young student discover the violin for the first time, or seeing a community begin to recognize the value of its own traditions. It’s in crafting a space where art isn’t separate from daily life, but woven into it, where creativity becomes a way of reclaiming identity and imagining a future. That, to me, is what a festival can—and should—be.”

For his June 28 concert, Coke will be playing on a 1927 Enrico Marchetti violin made in Naples. “This violin is one of my most treasured possessions—not just for its craftsmanship, but for the history it carries. It’s a gift from my father while I was still in the conservatory. I’ve played it in concerts far and wide, but it carries more than just music. It holds the weight of things never said, the hopes he couldn’t articulate, and the dreams he passed down the only way he knew how: through silence and offering. This instrument, like so much else in our relationship, was both a gift and a kind of riddle—beautiful, precise, and impossibly hard to decipher. I’ve come to understand that playing it isn’t just about sound. It’s about memory, legacy, and learning to speak through something that was once given in place of words.”

* * *

Coke Bolipata’s June 28 6 p.m. recital at Manila Pianos is free admission. Manila Pianos is located at the 4th floor, Ronac Lifestyle Center, Paseo de Magallanes, Magallanes Village, Makati City. The program is as follows: Kreisler’s Liebesfreud and Shon Rosmarin; Dvorak’s Songs My Mother Taught Me; Tschaikowsky’s Yearning Heart; Chopin’s C-sharp Nocturne; Massenet’s Meditation; Elgar’s Salut D’Amore; Ponce’s Estrellita; Moricone’s Cinema Paradiso; Bolipata’s Song of the Mermaid; Cruz’s Bituin Walang Ningning; Abelardo’s Cavatina; Cruz’s Sanay Wala Ng Wakas and Velez-Romero’s Velez/Romero’s Sa Kabukiran.)