‘I want a government that cares about us’: What youth voters want you to know this election season

Today’s kabataan are pragmatic. They dream in moderation, speaking about their ambitions with an edge of sarcasm or doubt, using careful words under the threat of disappointment.

When asked about the future they want, three things come up: a place they can easily rent, a well-paying job, and a Philippines that can only exist in fantasy. It’s as if the five interviewed students instinctively understood that they could not have the life they wanted without drastically changing reality.

“I used to want to become a nurse,” 19-year-old Xander, a senior high schooler, says, “but I learned recently not even nurses get paid well anymore.” Now, he doesn’t know what college is for, at a time when a degree doesn’t automatically lead to financial security and in a place where a better family name, patron, or generational wealth are your best bargaining chips for better opportunities.

Xander is also trans-masculine, but gender-affirming healthcare is far from his main priorities. He’d come to terms that he was “not in the right body” and not in the right country. Transitioning isn’t legally or culturally approved in the Philippines, and even if Xander could do it, it would be expensive. “I’d get a toy car instead,” he says, describing his goalpost for gender euphoria with a smile. “The remote-controlled kind. I wasn’t allowed to play with them, but I’d heal my inner child by getting one.”

“There’s a lot of fear and anxiety,” Justin, 21, a student activist, says. The disillusionment is a hydra with many heads: rising costs and consequences of living; erosion of trust towards the government and the media; political polarization and cultural tugs-of-war; constant systems-in-disrepair found in multiple levels of life; and a perpetual feeling of helplessness as a Filipino and a global citizen.

Today’s youth are tired and angry, and they want you to vote for a future they can look forward to because the present just isn’t cutting it.

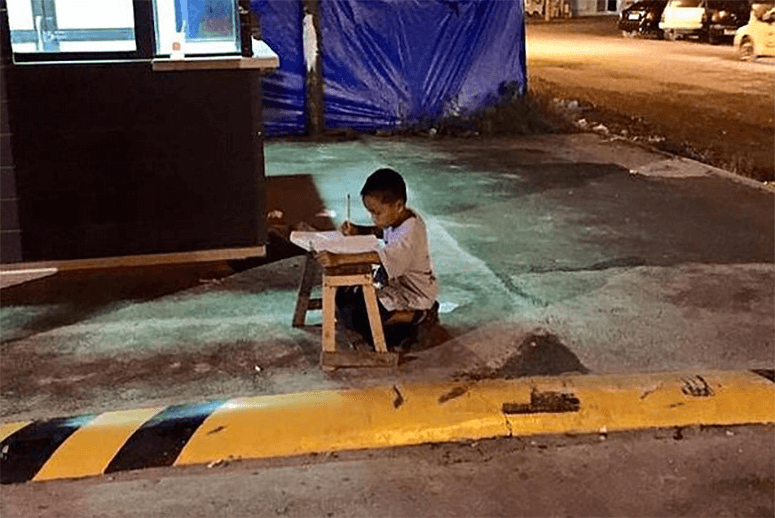

The Philippines is sinking, Palestine is burning, China is approaching, America is crumbling, and young Filipinos still have to cram homework, look for internship opportunities, and make class presentations. It is easier to set one’s goals on something within reach than feel the wave of helplessness from realizing the futility of being a person so displaced from power.

While their dreams are tempered on a personal level, imaginations run wild about what the Philippines could be. Hesitation drops, voices rise, and they rant about all the things they wish could change—not just for them, but for everyone. Far from sheltered balat-sibuyas, today’s kabataan are well-informed constituents who are acutely aware, to the point of existential paralysis, of the inequality, corruption and unsustainability in the world alongside the latest TikTok trends, distracting celebrity scandals, and ridiculous political drama. It is not enough if the world gets better for one. A country is not worth living in if it is not good for all.

Sol, 21, admits that they’re in a position of privilege. They’re a dual passport holder studying in a private university, yet they point out that if even they face difficulty in a system that does not serve them, “How much more difficult is it for people who aren’t?”

There are so many talented, smart, and passionate Filipinos, but the bridge to opportunities that would help them flourish is non-existent, and current opportunities, like scholarships, stipends and mobility programs, only value a very narrow few from very specific circumstances derived from social inequality. Instead of a system that ensures nobody gets left behind, the system has Band-Aid solutions for the problems it creates.

Sol hopes that, one day, lawmakers will see the Philippines as they do: a place that probably won’t make bank but is still worth cultivating, and this does not just include the people. Along the environmentally unsound reclaimed beach along Manila Bay, Sol has taken photographs of wild herons living among urban Filipinos, an ignored population in a city that believes itself set apart from the wild lands it used to be.

For Kyla, 21, her rage on behalf of the Philippines is similar to the rage one feels about a friend’s unhealthy situationship. “(Most of us) don’t know how easy it is for other people, (especially for people living abroad),” she says, impassioned, “and because of that, we don’t want more for ourselves. They lower their hopes, dreams and standards. They believe this is the best they can get.”

Just finishing an internship at a government office, Kyla has had a taste of adulthood and it has left a bitter taste in her mouth. Between hours-long commutes in and out of the NCR and witnessing firsthand the inefficiency and backlogs in government administration, Kyla wishes for more than the life she’s been told to settle for. “We need to hold our government to higher standards,” she says. “We’re paying them thousands of pesos in taxes. We aren’t paying them to punch people in teleseryes. We need to hold them accountable for the infrastructure and services that they should be giving us.”

Por, 21, a scholar and student leader—who asked to use a pseudonym for this article—is more blunt. “The future that I want is to be able to walk down the streets of my country without worrying about being shot (by the police),” she says, eyes blazing, sitting in her childhood home, near a street where such an incident occurred to a senior high schooler, “or without worrying about the bills, my education, or rights. I want to live in a country without (worrying about) survival.”

Student leaders like Por and Justin define their school years with a constant flow of extracurriculars, initiatives and outreach programs. That’s one good thing about living in a country that does not serve its people as well as it should. Students will always have something to do for their CVs. In another life, they would be seen as lawmakers-to-be, but Por and Justin don’t see many lawmakers that represent them, nor do they see an easy way into a political sphere dominated by clans and dynasties worthy of diagrams in a fantasy novel.

While the students interviewed can name the politicians, parties and officials they’re rooting for, avoiding, or outright disavowing, they often follow up with a resigned comment on how far these lawmakers can go in a system that disfavors everything the youth stand for. All eyes are on the people up top, and the view is unpleasant.

While this was not written for the lawmakers who have chosen not to listen, especially those who have broken their promises to the Filipino people, the kabataan interviewed have a lot to say about the candidates of the present and future.

“I want a government that actually, genuinely cares about us,” says Por.

“I want (politicians) to do their jobs,” says Kyla. “Being a politician should not be a side gig to being an artista or businessperson.”

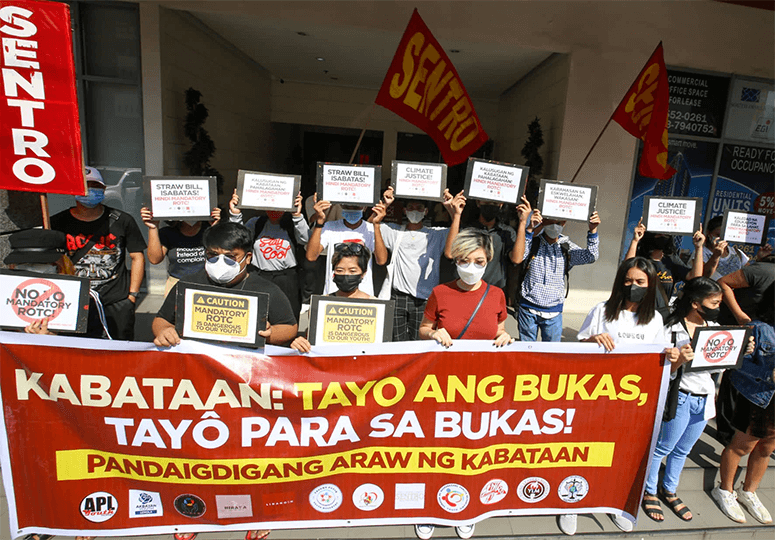

To the progressive parties in particular who say they stand with the youth, Justin says, “Fight the good fight. Remember the situation. Remember why you’ve been elected.”

But this is their message for you: they need you to realize you deserve better, and so do the people coming after you. This is not all there is. This is not everything that could be.

Choose leaders not based on their names or personas alone, but on what they stand for, what they’ve done for their communities, and what they could do.

Hold them all accountable. Circulate those sarcastic TikToks that throw shade at the questionable choices those in government make, back the youth-led lobbying groups that push your interests to the table, and support the press who watch these lawmakers vigilantly.

Most importantly, back each other up in the fight for each other’s rights. If no one at the top will do it, who else is going to?