Scandalous heiress Ida Rubenstein inspires a couture fantasy

Maurice Ravel’s Boléro, that hypnotic piece from the classical music canon, has always been on top of Stéphane Rolland’s list to track a runway show. Equally as compelling for him is Ida Rubinstein, the eccentric heiress who commissioned this musical score for her ballet which made headlines just as much as the many scandals in her life. The designer married the two in Argument, his FW2025 Haute Couture collection imagined as an encounter between the composer and the ballerina—a meeting of cubic shapes, baroque detailing and sensual style.

Born in 1883 into one of the Russian Empire’s wealthiest families overseeing sugar mills, breweries and banks, Rubinstein was orphaned at age eight, leaving her a vast fortune. Living with her aunt, the socialite Madame Gorvits, she grew up in a mansion in St. Petersburg’s famed Promenade Anglais and received the best education in theater, music and dance including lessons from instructors of the Russian Imperial theaters. She eventually made it to Paris where she set out to perform on stage as an actress, a profession that horrified her conservative Orthodox relatives who considered it no different from that of a prostitute. To make things worse, she had a penchant for nudity, coming out in various stages of “indecent” outfits which were enhanced by her tall, slender figure and striking profile. To save the family honor, a brother-in-law, Dr. Levinson, had her declared legally insane and committed to an asylum.

Upon her release, to earn her freedom and the right to control her fortune, she married her first cousin, Vladimir Gorvits, who was madly in love with her and allowed her to travel and perform. She ventured into dance which she actually had little natural ability for but nevertheless persevered in and made up for with her sensuality, causing controversy again when she stripped nude doing the Dance of the Seven Veils in Oscar Wilde’s Salome.

She danced with Sergei Diagilev’s Ballets Russes starting in 1909, partnering with the great Vaslav Nijinsky in Scheherazade, a hit in keeping with the Orientalist craze then. She left in 1911 to form her own company staging controversial pieces like Martyre de Saint Sebastien in which she played the lead and employed the best creatives of the day, including Michel Fokine for choreography, Léon Bakst for design, Gabriel D’Annunzio for text and Claude Debussy for score. With its stylized modernism, it was both a triumph and a scandal, causing an uproar from the Archbishop of Paris who prohibited Catholics from watching because the saint was being played by a woman and a Jew.

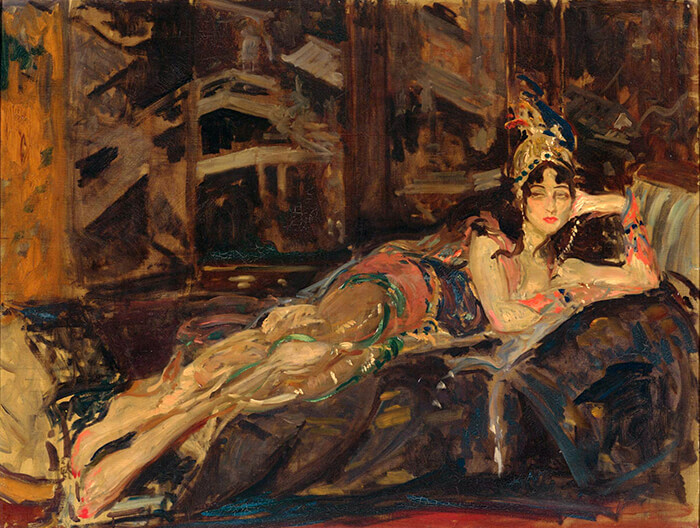

Unperturbed, she commissioned many more lavish productions, establishing herself as a patroness of the arts. She was also much celebrated in art, with portraits by great artists, and became a style setter wearing the latest couture creations, surrounding herself with the opulent and the exotic, going on big game hunts and living among wild cats. At home, she kept a leopard cub and even a panther who once came close to attacking Diaghilev who never forgave her. She further shocked the public with her lifestyle, having romantic relationships with both men and women, including an affair with the painter Romain Brooks who marveled at how she had “an elusive quality, expressing an inner self that had no denomination, a gift for impersonating the beauty of every epoque.”

One of her most lasting legacies, however, would be Boléro which she asked Ravel to compose for her Spanish-themed ballet. It became a very personal project for the composer, referencing the rhythmic sounds of belts, whistles and hammers from machines in the factory that his father took him to as a child, the berceuse melodies that his mother sang to put him to sleep, and the bolero dance from her Spanish roots, to build a piece around a single repetitive melody, gradually increasing the dynamic level and instrumentation into a glorious climax. With a hard driving rigor, the music was a direct contrast to Rubinstein’s romantic style in the ballet that premiered at the Paris Opera in 1928, a juxtaposition that Rolland exploited for his collection—reflecting this interplay of opposing forces and the creative tension between the composer and the dancer, masculine and feminine, structure and fluidity, restraint and opulence.

Rolland’s show itself was a theatrical event with a live performance of Boléro by an orchestra, set at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées where, significantly, the Ballets Russes, with whom both Ravel and Rubinstein collaborated, first presented their groundbreaking work.

Ravel’s music, with its repetition and crescendo, is echoed in structured silhouettes and sharp tailoring with a modern edge, almost Japanese in style, while Rubinstein, known for her dramatic stage presence and unconventional style, is evoked through the collection’s bold colors, Spanish influences and sense of theatricality. A range of pieces includes tuxedo dresses, samurai-inspired silhouettes, and poncho-style gowns in mousseline and crepe that floated around bodies, all designed with meticulous attention to detail like red dresses embroidered with crystal and coral as well as black organza matador vests, capes and belts. Sculpted geometric headdresses and hairstyles shaped like musical notes completed the ensembles.

The collection, a virtual symphony of shapes, transcends mere clothing by becoming a statement about the power of art, music and performance in shaping our perception of fashion.