The cool face of lace

Many of our memories of lace are at church ceremonies: our christening attire, our mothers’ veils for Mass, our sisters walking down the aisle, our mothers’ widow’s weeds. Very serious, if not profoundly solemn. But lace was fun, too: the lace minis of the ’60s from Aureo Alonzo, picking up from Mary Quant and Biba in London; and lace shirts for clubbing from Ernest Santiago.

Lace never really went away, though they have had a tendency to come out in stuffy iterations. But recent runways have resurrected them in the unlikeliest colors, cuts, and combinations that have made them cool again.

With our weaving and handcrafting heritage, it was natural to lean into lace. During the Spanish colonial era, lacemaking and embroidery were introduced in church schools and found their way to local fashion’s traje de mestiza. During the American period, the craft was promoted in public schools as a practical skill and source of income.

A notable type introduced was bobbin lace which the Belgian nuns of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (ICM) brought to Sta. Barbara, Iloilo and Tagudin, Ilocos Sur.

This lace was made into collars, napkins and trims. Bobbin lace edgings in abaca from Capiz, dating from 1910, have been spotted at the Smithsonian.

Open woven fabrics and fine nets with a lace-like effect have been around for centuries before the establishment of the great European lace houses. Early references to lace refer to ties, as this was the primary meaning of the word until well into the 17th century.

There is pictorial evidence from the late 15th century of simple plaited laces used on costume and a bobbin lace pattern book printed in 1561 states that lace was brought to Zurich from Italy in 1563. It was certainly in the second half of the 16th century that saw the rapid development of lace as an openwork fabric created with a needle and single thread (needle lace) or with multiple threads (bobbin lace). By 1600, quality lace was being made in various centers including Flanders, Spain, France, and England.

Fashion certainly drove lace production: Ruffs and standing collars demanded bold geometric needlelace at the end of the 16th century and softer collars of linen bobbin lace took over in the early 17th century. The refinement of the 18th century required the delicacy of French needle laces of Argentan and Alençon and Flemish bobbin laces of Binche, Valenciennes, and Mechlin, dominating a market that prized items like cravat ends and lappets to display wealth and good taste, not to mention power.

In some places, laws were actually passed to limit who could wear certain kinds of lace. With the extravagant amount spent on the material, its importation was banned in some countries, but smuggling was still rampant.

Although both men and women wore lace, it was not until the 18th century when it acquired a fully feminine character as men renounced it and began to integrate it into the multiple layers that made up women’s underwear, giving it boudoir associations carried on until the Victorian era.

During this time, machines shifted its consumption from aristocratic circles to the growing middle class. Handmade lace still remained a luxury item, however, in a changing world of consumer culture and mass fashion. Lace also became tied to wedding traditions after Queen Victoria’s highly publicized lace-trimmed bridal dress.

In the early 20th century, lace transformed from prim to edgy with the flappers who layered it under fringe or styled it with sequins. Around mid-century, it was identified with style icons: Audrey Hepburn, dressed by Hubert de Givenchy in an LBD and mask in the 1966 film How to Steal a Million, imbued black lace with an air of mystery while Grace Kelly’s 1956 wedding gown by Helen Rose gave white lace a spirit of sophistication and purity.

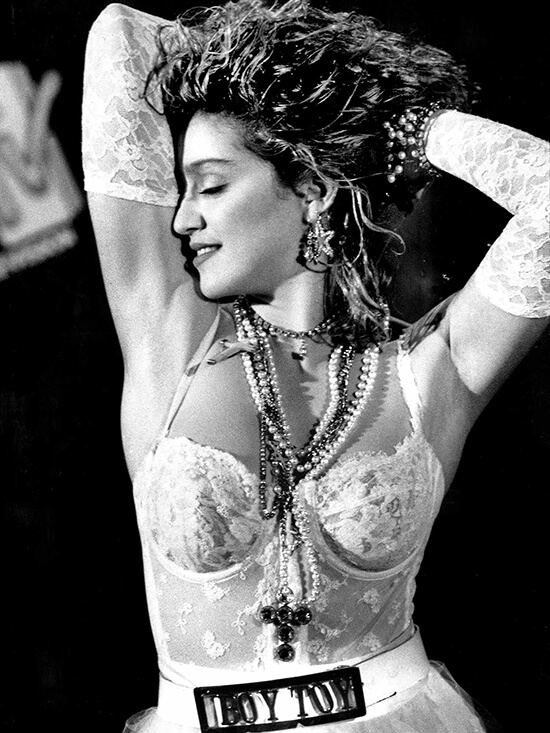

On the other end of the spectrum, lace acquired a subversive streak in punk iterations which came out in the 1970s, paired with leather and studs. Shortly after, the gothic subculture of Vivienne Westwood and The Cure propelled lace to even darker, theatrical territory. Meanwhile, Madonna’s 1984 Like a Virgin look of lace gloves and lingerie-inspired dresses projected a rebellious innocence with sexual undertones. The ‘90s minimalism reduced lace to barely-there trims on slip dresses worn by supermodels Kate Moss and Naomi Campbell.

Perhaps as a reaction to the Quiet Luxury of the past seasons, the maximalism of lace is making a strong comeback, moving easily between relaxed boho looks like Chloe’s ruffled blouses and ethereal dresses and the dark romance at Balenciaga. McQueen and Versace offer an early 2000s take with asymmetrical skirts while Gucci has fun leotards in neon hues. Filipino designers reimagine Filipiniana by mixing lace with piña and other fabrics: Lulu Tan Gan in her signature layering for easy, chic ensembles; Paul Cabral and Dennis Lustico through their impeccable couture ternos and barongs.

With all its reinventions, lace proves its versatility with different moods one can create and with different combinations to keep it looking fresh and updated. In styling lace, it’s really all about balance—not making it overpower your overall look while mixing it with other pieces in your wardrobe to fit your life and your style.