The wonder of Pinoy pop culture, as archived by ‘90s Kabaklaan

For the chronically online generation, doomscrolling is practically a reflex.

Since the world’s first foray into digital possibility, social media has morphed into many things: go-to news source, therapy substitute in the form of cat videos, dopamine provider where bootleg movies meet celebrity gossip and porn, political theater engined by memes and TikTok videos, and artificial intelligence safe haven where we’d rather ask Grok or ChatGPT for literally anything than read and think. It’s a ragebait wasteland in which we’re all trying to be “thought leaders,” or “the Renata Adler of looking at (our) phone a lot.” Sorry, Ann Manov.

But for a curious, and sometimes horny, corner of the internet, it’s a way of revisiting the heyday of Pinoy pop culture when printed matter and physical media were still so in vogue, particularly for the 148K audience of ‘90s Kabaklaan, the in-demand Instagram archive for local celebrity culture of the 1990s and 2000s. ‘90s Kabaklaan is to Instagram as Glossy Archive is to Twitter (or X, if Elon Musk is to be taken seriously).

Back then, “the concept of consuming media,” which causes some insufferable cybernauts to crash out from time to time, didn’t seem so foreign to the thirty-something Victor, the anonymous showrunner behind the online catalog. Raised by his grandmother in Tarlac province, Victor lived a simple yet sensuous life. The youngest among his cousins on his mother’s side, his fascination with printed ephemera began with buying issues of the ‘90s staple Pilipino FUNNY Komiks in street stalls.

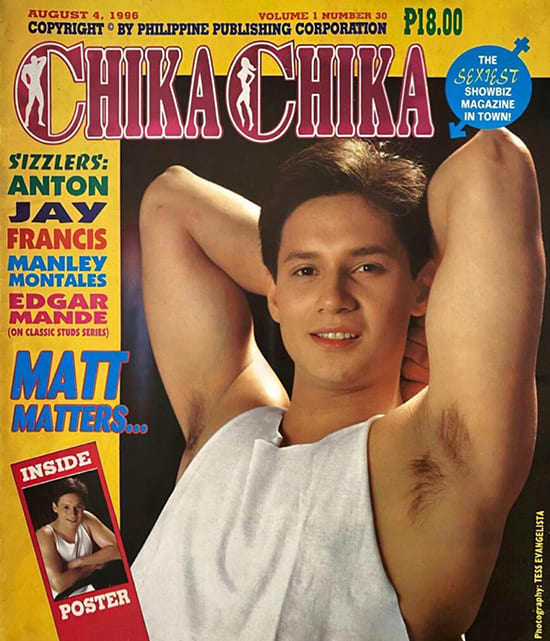

Initially, he practiced his drawing skills by reading comics and watching anime, until his sketches fixated on the male body. “Parang (sa) Dragon Ball, malalaki ‘yung chest, malalaki‘yung biceps, putok ‘yung abs,” he tells me. That’s one way to let your intrusive thoughts win. Then followed his exposure to tabloid erotica and showbiz magazines like Chika Chika, sold next to the stalls that offered his favorite comic strips.

Victor was able to explore on his own as both of his parents worked abroad at the time. “I think that contributed a lot (to) developing my own interest, my sexuality,” he says. Just as ‘90s and 2000s teen magazines served as guiding figures for girls, he found comfort in erotic glossies, as he grew up an introvert given the age gap between him and his elder sibling and cousins. “Wala talaga akong makausap about those kinds of feelings, so I was really just with my own magazines.”

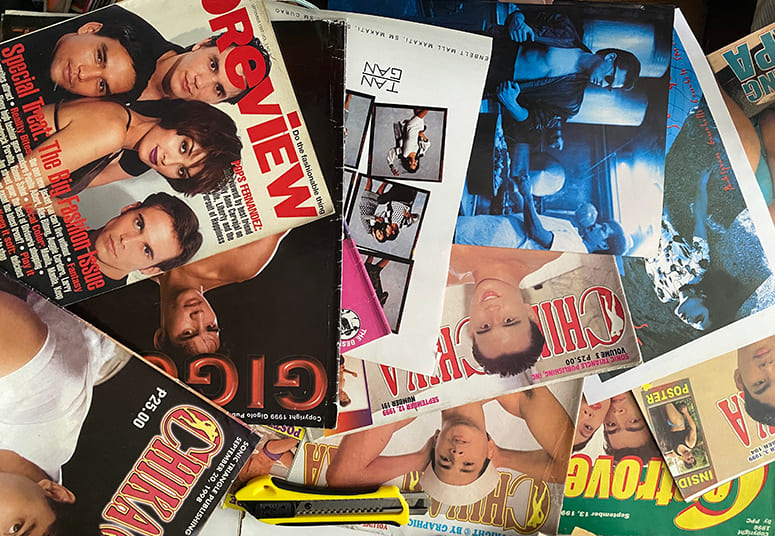

It wasn’t until three decades later that his magazine collection, often purchased in bulk in Manila’s Recto Avenue, expanded and found new life online. In July 2021, at the height of COVID lockdowns, Victor birthed ‘90s Kabaklaan as a way to preserve his vintage magazine copies, which were already beginning to deteriorate. “Sayang naman kung hindi makikita ng ibang tao,” he points out.

When we spoke over Zoom, ‘90s Kabaklaan was about to mark its fourth year. In its infancy, the online archive was remotely populated by libog-inducing images of sexy men and was even flagged by Viva Films on Instagram, until it evolved into a solid Pinoy pop culture hub that dutifully features magazine shoots, music, motion pictures, and television from the ‘90s and early aughts, often marketed through Gen Z’s lingua franca: memes. Through its vibrant spreads and repurposed film snippets, it harnesses the liminal edge between analog nostalgia and digital magic.

“The ‘90s, I would say, are the glorious years of Pinoy pop culture kasi we just came off a tyrannical regime,” says Victor. “There was a sense of liberation (in) expressing what you wanna do and what you wanna say. So, nawala ‘yung censorship from the Marcos regime, and it shaped a different era of kabaklaan altogether. Nagkaroon ng bomba films, nagkaroon ng sexy films na mas laganap. And nag-flourish ang magazine publishing industry natin in the ‘90s.”

The pivot in the catalog’s content came as the page grew its reach, “exploring other sides of kabaklaan,” as the archivist puts it. Its followers now include the likes of entertainment reporters MJ Marfori and Nelson Canlas, magazine editors Myrza Sison and Leah Puyat, and OG “it girl” Tweetie de Leon-Gonzalez, who fronted Preview’s 1995 maiden issue. “So okay, more fashion (content), more glossy,” shares Victor. “Magpo-post ako ng something society, until sa nagkaroon na ng memes, nagkaroon na ng music. It became a reflection of the community.” Never underestimate the power of a scanner and a dream.

A fraction of ‘90s Kabaklaan’s cult following also contributed scans from their own archives, which the page would post as collaborations. In rare instances, some followers would send physical magazine copies, but Victor isn’t always keen on this gesture for his privacy. “Baka it’s a free pass na mag-reveal ako,” he notes.

For the blissfully uninitiated, ‘90s Kabaklaan, despite its quintessential curation, is sustained by a one-man team. Victor is an archivist, curator, content creator, and social media manager rolled into one. Talk about the noble task (i.e., invisible labor) of being “in queer media,” all the while “holding space” for his 9-to-5 job in finance. “I think sometimes it’s better to slow things down, and not really focus on growing the account but more on connecting well with the audience,” he says. “I think that’s more important.”

Still, the showrunner stays optimistic about the archive’s potential. “Sobrang gandang paglaruannitong ‘90s Kabaklaan,” he tells The Philippine STAR. “It can be a jumping-off point to other avenues.” He thinks of turning the catalog into a podcast or educational TikTok bites tackling online disinformation through a queer lens. Unfortunately, he lacks the deep pockets to do it. “Promise, like it will benefit the community sana talaga with the audience it has built throughout the years,” he surmises. “Ang ganda sana.”

The ‘90s, I would say, are the glorious years of Pinoy pop culture kasi we just came off a tyrannical regime. There was a sense of liberation (in) expressing what you wanna do and what you wanna say.

The catalog’s steady torrent of pop culture paraphernalia from the glorious era led to The ‘90s Kabaklaan Show, a one-day exhibit at the Archivo 1984 Gallery in Makati in January 2024. Mounted over three weeks, the exhibit was a collaborative effort between Victor, Archivo founder Marti Magsanoc, and SPOT chief editor Jerome Gomez.

“Grabe that night,” Victor recalls. “Never in my wildest dreams na magkakaroon ng exhibit si ‘90s Kabaklaan. It was well attended.” The demographic was a big deal for the show. “Kailangan it’s representative of everyone: sosyal, jologs, bakya, hindi (lang) alta.”

The exhibit doubled as a way to wrap up the Instagram account’s ‘90s era as it turned its focus to Y2K Filipino pop culture, shifting from gay awakening to girlhood, just as the country embraced digital charm in the early aughts. “It was the advent of the internet, so you can see a lot of influence from social media, the early rise of the phones, then ‘yung mga forums, blogs,” recalls Victor. The 2000s also saw network wars, which animated the consumption of local pop culture. Love teams, noontime TV rivalries, scandals, and celebrity gossip before the 6 p.m. news were basically a national pastime.

But like many local print titles that migrated to digital only to fold later on, Victor reckons that ‘90s Kabaklaan isn’t suited for Instagram longevity. Once the page reaches its fifth year and exhausts its Y2K content, the creator intends to stop posting altogether, though the page itself will still be up. “There’s so much you can post lang, eh,” he explains. “Paano ‘pag naubusan ka ng archive, ‘di ba? What’s next?”

Half an hour into our conversation, Victor reveals the page’s pipeline. “I’ll do a little bit of touch lang on 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008 maybe, kasi right now the timeline of the page is 2000 to 2004 lang, so Y2K basically. And then pahapyaw ko ‘yung late 2000s and then I’ll do a month na puro ‘90s ulit, like going back to the roots of the page.”

“I still have the drive, but it can only go so much,” he continues. “Wala nang nostalgia factor if it’s like 10 years ago lang kasi parang kahapon lang ‘yon, e. With the 2000s kasi there’s a bit of a wonder-like feeling.”

Though the internet has democratized people’s access to cultural conversations, it has also diminished the value of print. Bite-sized content, emboldened by influencer culture, is all the rage now, while longform is endangered. It’s kind of ironic that ‘90s Kabaklaan finds a stalwart audience in the very space that killed the physical ephemera that it spotlights. But despite the odds, print endures.

Victor says print media is a “premium” experience. “It transports me back to a simpler era,” he insists. But it’s also premium in the sense that today’s local magazines are priced at about P500 per issue, just a few hundred short of Metro Manila’s minimum wage. “I really think the editors or the publications should select the cover star or the articles that (are) meaningful talaga to the brand that they’re pushing,” Victor adds, noting how some current print titles tend to be homogeneous.

Beyond this, printed matter cultivates a stronger reading public, in which the Philippines, with its education crisis, painfully lags behind. “When you flip through print media, the articles (themselves) are edited by professionals and have been overseen by competent editors, so it will force you to think critically, and it will force you to be more creative,” Victor explains. “And it’s something na lacking kasi right now we’re so used to scrolling through the article, we really don’t read. If you can purchase the magazine, you’re forced to read the article, you’re forced to read the interview, you’re forced to read the information.”

As our interview wound down, I pressed Victor about ‘90s Kabaklaan’s final pasabog, and the anonymous archivist says he intends to unearth the treasured pieces in his sizable library, including some never-before-seen Gimik posters and photos, and over 200 unique issues of Chika Chika magazine that he owns. “I call it the best of the best,” he says. “Walang meme, walang video, walang anything, walang patawa, walang humor. Gusto ko ‘90s photos (lang), best of the best.”

At the same time, he plans to hold a closing exhibit to mark the catalog’s projected five-year run. “It will be curated by not just me, but with my trusted (people) sa buong sangkabaklaan,” he assures. “I will try to involve as many people as possible to contribute their own photos. I really want it to be as inclusive as possible.”

It’s kind of ironic that ‘90s Kabaklaan finds a stalwart audience in the very space that killed the physical ephemera that it spotlights. But despite the odds, print endures.

‘90s Kabaklaan began as a frantic impulse in a precarious time. Its primary draw is sweeping nostalgia, burnished with its hyper-specific brand of funny and horny. It afforded us access to a kind of life leagues away from the lives that we lead now. It is peak pre-internet desire. But what ultimately emerged from it is a community that prohibits the pages of Pinoy pop culture from ever snapping close. More profoundly, it offers cultural workers and tastemakers both a premise and a promise.

If he’d be so lucky to be given access to the 2000s library of media outlets like ABS-CBN and archived footage from definitive documentary shows like Probe and i-Witness, Victor won’t shy away from embracing the more political corner of local pop culture. “Hindi naman to weaponize but to make people aware that these things actually happened and we should learn from the past and we should not forget our history,” he says.

But as it is, ‘90s Kabaklaan has already done its part. Honestly, Pop Crave should be taking notes by now.