The young fashion designer reimagining local and narrative weaves

When a professor asked her to describe what kind of consumer would be drawn to her graduation collection with one word, Anne-Marie Dimanche responded, “Opinionated.”

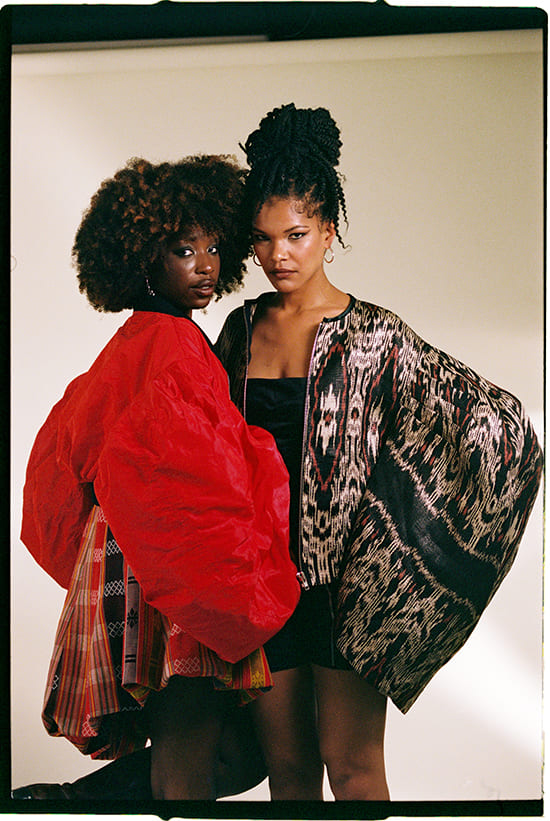

In late June, in a humid warehouse in North Amsterdam as Japanese metal music screamed from the speakers, DOG EATER dominated the runway with its loud Filipino weaves and audacious silhouettes. Distorting the Maria Clara and employing the fabrics from the indigenous peoples of South Cotabato, Ifugao, and the Cordillera Region, DOG EATER was less an opinion and more of a statement. It was the final exasperated breath of someone tired of rigid narratives.

Dimanche’s own story of getting into fashion was a break from expectations. Arriving in Amsterdam in 2018 to pursue biomedicine, she abruptly switched to the arts in 2021 after realizing that a life in medical research wasn’t for her, despite constant reminders that it held more financial stability. “I think I’ll want to die if I hate doing what I have to do every day,” she said.

“I always wanted to do something creative,” she continued, rubbing her tattoo-covered arms. “It’s something that felt intuitive. Nothing ever felt intuitive. During COVID, I would play dress-up, and my friends and I would do makeup and take pictures everywhere. (...) Fashion also felt very interdisciplinary.” She added, laughing, “You can actually have job prospects, compared to painting.”

Switching tracks was not the only struggle she faced in art school. At the Amsterdam Fashion Institute, her unrelenting and persistent work ethic was seen by classmates as an attribute to her being Asian and not an inner passion for the art she was creating. Walking around Amsterdam was a game of Russian roulette with her fair skin and slanted eyes: would she be catcalled with yet another badly-accented “nǐ hǎo”?

But as much as she was pigeon-holed into the role of a hard-working, submissive Asian, Dimanche could bite. These events didn’t embarrass her: she talked about them with a roll of her eyes and a sneer. She was no stranger to being othered. She’d grown up mestiza in the Philippines due to a Belgian grandfather and knew what it felt like to be foreign.

The title of the collection itself came from an incident where a European classmate jokingly asked her in a conversation about the ethics of eating meat whether Dimanche would “eat her dog.” Touching upon her inner instigator as she began conceptualizing DOG EATER, Dimanche noted down vaguely racist or ignorant comments she heard in class and tacked them on the board of her work station for all to see.

Her motto in design was this: “If you’re going to say something, say it with your whole chest.”

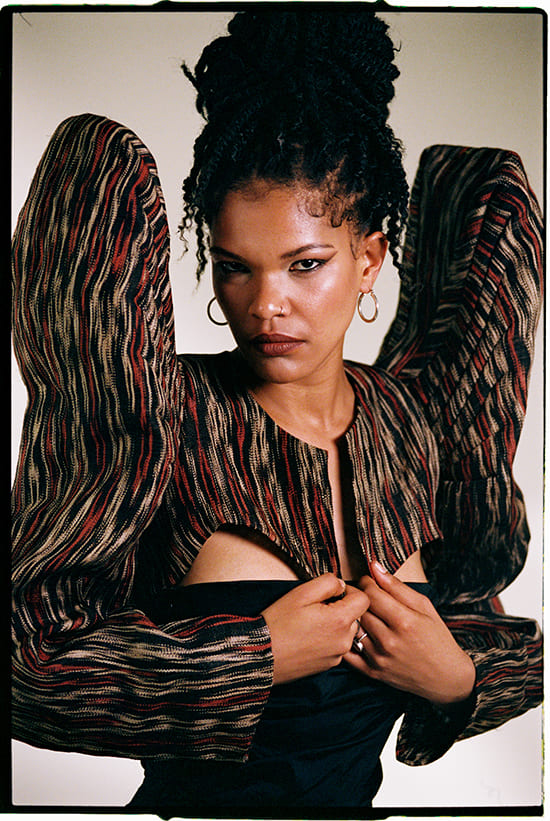

DOG EATER is made of six ensembles, highlighted with a statement piece made of fabrics from different regional communities. The camped-up and dramatic proportions of the butterfly sleeves found in the collection parody the traditional Maria Clara dress’ representation of dainty Eurocentric beauty, overriding the standards with fabrics from communities whose oppression began in the colonial era and whose struggles still remain today.

Using fabric like tenalak was challenging to sew with for the first time, with the added pressure of having so little of it. Dimanche only got a few samples from her first trip back to the Philippines after living in Europe for five years. For one of the sleeves of a bomber jacket, Dimanche had to resew it three times due to prior mistakes, each time fretting about overworking the precisely-woven tenalak. However, Dimanche was adamant in using these fabrics to showcase the diversity of people across the Philippines and to break the convention of restricting the use of regional fabrics solely for traditional costumes.

Among all the narratives DOG EATER aimed to break down, Dimanche looked forward to reclaiming piña silk from the legacy of the Marcoses. For a paper in fashion theory, Dimanche found herself in a rabbit hole of how former First Lady Imelda Marcos used culture and clothing as tools for myth-making, including the popularization of Filipiniana made of piña silk. In doing so, piña silk had become synonymous with the arts, wealth, and tradition with a dash of political corruption and violence.

While sourcing the fabrics for her collection, Dimanche spoke to another designer with an interest in Filipino weaves. The designer opined that political leaders after the Marcos dictatorship should not have shied away from piña silk. Otherwise, they could have reclaimed this politically-charged fabric and transformed its meaning. In employing fine, gauzy piña silk for a barrel-like modern rehash of terno sleeves from a time before the Marcoses, Dimanche hopes to do just that.

Despite everything, though, Dimanche is careful to say she’s “reclaiming” anything. She herself is not an indigenous person, and their fabrics and stories are not hers to reclaim. Also, due to her privilege, she is insulated from a lot of issues that concern many Filipinos. That does not mean she has no stake in shaking colonial and political narratives.

Europeans see my collection as ‘ethnic’. Only Filipinos can truly understand.

Dimanche’s realm of rebellion is in fashion, and the battle she’s fighting is cultural and historical. It’s a new myth she’s making—one of punk princesses who are too Other to be from one place or another, who acknowledge the complex racial histories of punk and colonialism, who refuse to take injustice lying down.

When talking about using fashion as a cultural clapback, Dimanche brings up how the ilustrados focused on the arts as their battleground during the tail end of Spanish colonization, using the arts to fight racist and imperial ideologies. Coincidentally, Dimanche’s work and background remix this tradition, and like the ilustrados before her, she’s aware that Europe is not where her audience resides.

“Europeans see my collection as ‘ethnic,’” Dimanche said. “Only Filipinos can truly understand.”

Thinking of publishing her concept book for DOG EATER in Amsterdam and the Philippines after the school year ends, she hopes more Filipinos will be able to access her collection and resonate with what it stands for. As for herself, Dimanche hopes to one day work with and learn from the weavers who made her final project possible, to better learn about the roots of the craft—and shake up all the narratives.